The rumor of his death fueled the revolution

Download image

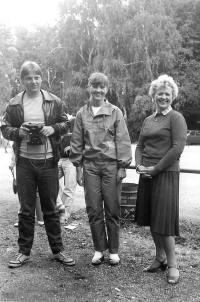

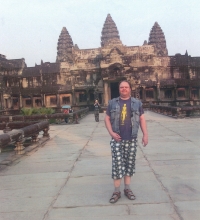

Martin Šmíd was born on 27 January 1970 in Beroun. After graduating from high school in 1988, he started studying at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics of Charles University. He was not politically involved and did not take part in the student parade on 17 November 1989, which ended in a brutal crackdown by the forces on Národní třída. Nevertheless, his name is inextricably linked with the history of the Velvet Revolution. It was the rumour of the death of the “Matfyz student” Martin Šmíd that gave it a significant impetus. On Sunday, 19 November, a witness learned that his picture was “hanging in Prague”. On the same day, criminal and state police came to his home to investigate. He then filmed a spot for Czechoslovak Television in which he confirmed that he was alive - just like his namesake and schoolmate; two Martin Šmíds were studying at Matfyz at the time. The police then apparently guarded the witness for several days. The officers spent the night from Sunday to Monday in the living room of the Šmíds and on Monday morning they took the young student to school. There, however, a strike was already underway, which he then joined. After the revolution he returned to his studies, finally graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture in 1988. Martin Šmíd worked with computers and led a happy life. In 2023 he lived in Beroun.