After years of Communist decay, people were hungry for something meaningful and useful

Download image

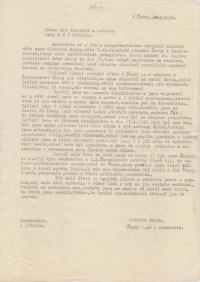

Oldřich Sojka was born on 20 September 1944 in Pilsen. His father, Oldřich Sojka Sr, was assigned to forced labour at the Škoda Works there at the time while also serving in the Luftschutz, an anti-air defence organisation. The Sojkas’ house was hit during one air raid, but luckily they were hiding in a nearby bomb shelter at the time. They lived with some friends until 1947. After the war his father renewed the family firm that produced metal furniture. He rebuilt the house and was employed as the national administrator of a large company in Cheb. Oldřich’s mother Marie, née Hošková, took up management of the family business in Pilsen. Following the Communist coup in February 1948, the family business was confiscated. Oldřich Sojka Sr was arrested by State Security in 1950. His case was part of the fabricated charges and show trial of Operation Olga. He was lucky - after enduring a year and a half of cruel imprisonment in custody, he could return home and begin earning the family’s living as a craftsman. In 1953 the family was forced to move to Úterý in the northern part of the Pilsen Region. They were not allowed to return to Pilsen until 1959. Oldřich did not receive recommendation for further study, and it was only thanks to his father’s contacts that he enrolled at an eleven-year school in Pilsen. A similar process awaited him in his efforts to study medicine, which he did not complete. He passed another set secondary-school finals as an X-ray laboratory assistant. In the 1960s he worked in the health sector. In spring 1968 he married. He witnessed the dramatic moments of the Soviet occupation in Planá near Mariánské Lázně and in Pilsen by the radio building. He started studying medicine again and graduated from the Third Faculty of Medicine of Charles University in 1973. As he claims, he has worked a total of fifty years at the Municipal Public Health Office in Pilsen. After 1989 he was active in the city council and in the Czech Social Democratic Party.