It was only up to us whether we would accept that role

Download image

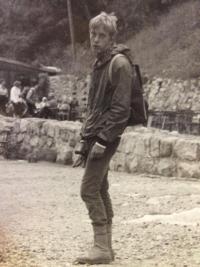

Tomáš Šponar was born on September 6th, 1968 in Svitavy as the only child of his parents. In the mid-1970s the family moved to Ústí nad Orlicí, where he studied the elementary and grammar school, from which he graduated in 1985. In the same year he began studying at the Institute of Mechanical and Textile Engineering in Liberec. During his studies there, Tomáš was active in the student theatre ensemble T. S. Garp, which was under the patronage of the Socialist Youth Union. On August 21st, 1988 he went alone to Prague to join the protest rally on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies. He marched through Prague in a crowd of protesters. On November 16th, 1989 he arrived to Prague with the theatre ensemble to participate in a festival of university art ensembles and on November 17th he travelled with the ensemble to Karl-Marx-Stadt (present-day Chemnitz) to a theatre festival of universities from communist countries. After his return to Liberec on November 19th and learning the news from Prague about the events on Národní Street, Tomáš immediately joined the students activities. On November 20th he became a member of the strike committee and he was actively involved in the student protests until the election of Václav Havel for president in December 1989. He completed his university studies in 1991. In 1998-1999 Tomáš converted to Christianity. Tomáš worked in press and in television. He and his wife live in Prague and they raise their three children. In his free time he enjoys running.