My husband said: When I was handing them the American passport, my hand was shaking

Download image

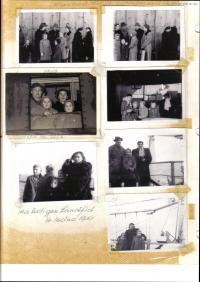

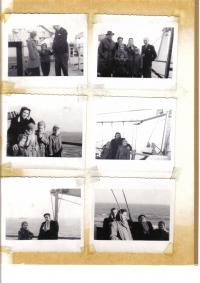

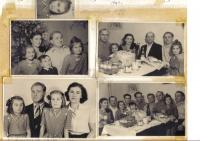

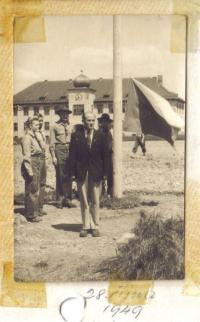

Anna Šrotýřová was born September 16, 1920 in Zdíkov, in the Šumava Mountains. Her father, who had fought at Piava in WWI, fell ill and died soon after his return from the army. The family inherited a small village pub with a tobacconist shop from him. Anna lived in Zdíkov throughout WWII and she met her husband-to-be Jan Šrotýř there. After the war they moved to Kvilda, where her husband worked as a financial guard. After the communist coup in 1948, he and his colleagues helped those who were threatened by the new political regime to illegally cross the border to the West. He fled to Germany on December 14, 1948, immediately before he was to be arrested. His wife and two daughters followed him six months afterwards. They spent the rest of 1949 and 1950 in Murnau, Bavaria, in a camp for refugees from communist countries, and then they travelled by ship to the USA. They spent their life in Chicago and in nearby Berwyn. Mrs. Šrotýřová returned to Zdíkov only after the death of her husband.