Speak up when something bad is happening

Download image

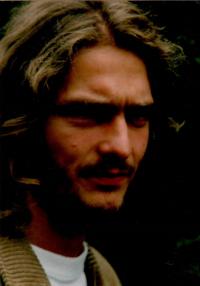

Martin Štainer was born on 25 November 1967 in Valašské Meziříčí. During his childhood and adolescent years he formed close connections with the local culture scene and made friends with a number of musicians who were persecuted by the regime or under surveillance. He was also active in both the Pioneers and the Socialist Youth Union. However, for a long time he did not see the organisations’ connection to the Communist Party. His first clash with the state came at grammar school, when he wrote an article for the student magazine. He did not hide his opinions. In the 1980s he performed a pantomime caricature of a Party meeting with his friends at Rockfest, which was officially organised by the Socialist Youth Union. State Security threatened to charge him with defamation of the state symbol. He came under regular surveillance at university in Olomouc, and he was repeatedly threatened with expulsion from the school. In November 1989 Martin Štainer was one of the student leaders of the Velvet Revolution. He now directs his own company and lives in Olomouc.