“The first one: The one who wants looks for ways. The one who does not looks for reasons. And the second: Where there is a will, there is also a way. These are two maxims which I follow.”

Download image

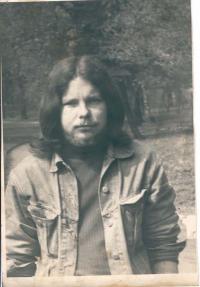

František Stárek, nicknamed Čuňas (Porky), was born on December 1st, 1952 in Pilsen. While still a pupil at an elementary school in Teplice, he discovered the Beat of culture, and from the sixth grade on, he fought for the right to have long hair. After graduation, for which he sat in a short-haired wig, he left Teplice. He found employment in Prague, where he befriended members of the local underground scene. He decided to gradually break through the limits of the Prague scene in order to reach other unofficial communities outside of Prague. Based on previous plans for an independent medium for the underground scene, which were never put into practice, he began publishing the Samizdat magazine Vokno (Window) in 1979. He already had an eight-month imprisonment in the Pilsen-Bory prison from 1976 under his belt. He was later sentenced in the trial against the band The Plastic People of the Universe. None of the initiators of the trial could anticipate that this unjust verdict against the band’s members would serve as a link between the two worlds which had hitherto been separated, and eventually give rise to Charter 77. Stárek himself signed it as early as 1977. Two years later, when the political regime began with severe repressions in response to Charter 77, František Stárek co-founded a commune in Nová Víska near Kadaň. A huge farming estate with a large barn served as a private scene for underground concerts and cultural events. In 1981, the farm was expropriated by the state, and by the pressure of the Secret Police, the community did not manage to purchase another place. After the community had been disbanded, Stárek was imprisoned for two and a half years for the publication of Vokno. Before that, the Secret Police provided him with an exit permit, hoping that Stárek would emigrate on his own accord. Instead, Stárek used the opportunity to make a trip to Poland, where he met top representatives of the Polish underground and supported the Solidarity movement which was formed at the time. After his release from prison in 1984 Stárek carried on with his publishing activity, in spite of the burden of two-year monitoring which nearly equaled serfdom. Together with filmmaker Michal Hýbek and other friends he contributed to the production and distribution of the Original Video journal, which was distributed through similar channels as the Samizdat Vokno and which was presenting film documentaries about art, the dissident movement or ecology. Vokno also continued to be published. As an editor-in-chief, Stárek and Ivana Vojtková, his wife-to-be, were arrested again in February 1989 and sentenced to two and a half years of imprisonment. He spent November 17th in prison and he was released on December 26th, 1989 following the presidential amnesty. In the following years, he joined the counterintelligence department, where he remained until 2007. At present, he is employed in the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes and he focuses on a research and documentary project about the history of Czechoslovak underground. In his free time, he studies family genealogy and organizes underground festivals.