I studied in local history at a time when there was almost no interest in such subjects

Download image

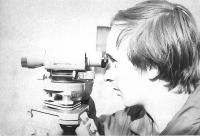

Karel Stein was born on 9 September 1954 into a Germa-Czech family in Varnsdorf. His father raised him up to take an interest in nature and the countryside. At primary school he joined a tourist club and met with Mr Bienert from Šluknov, who further developed his love of local history. As an adult he transformed this hobby into a systematic discipline. Karel Stein researched German literature, visited local witnesses, compiled maps of local names, and recorded approximately two hundred testimonies. He used the most interesting material when writing his book Pomníčky Lužických hor a Českého Švýcarska (Memorials of the Lusatian Mountains and Bohemian Switzerland). After university, Karel Stein worked as a surveyor at Building Structures Děčín for ten years. He then found employment at the Administration of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains PLA (protected landscape area), where he remains to this day.