Serve your homeland firmly!

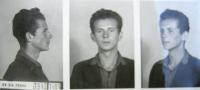

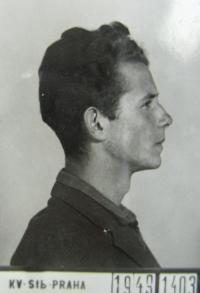

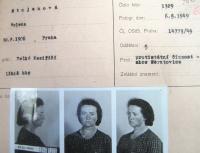

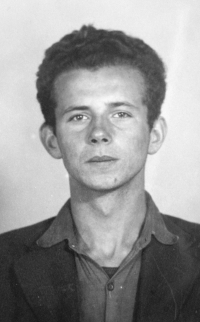

Download image

Jaromír Stojan was born February 21, 1929 in Prague. His father Jan worked as a train supervisor and his mother Helena was a dental nurse. Apart from Jaromír they had one more son. The family moved from Prague to Libiš, where Jaromír attended elementary school and where he lived basically until he got released from prison. He attended a higher elementary in Neratovice and then trained as a gardener. During his vocational training, he was gradually learning details about life in the USSR from his boss, who came from Ukraine, and this formed Jaromír’s opinions after the war. The entire family survived the war. Like his father, after the war Jaromír Stojan joined the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party and his mature political opinions eventually led to a conflict with a local district communist secretary of the Mělník region. Stojan was appalled when he saw former collaborationists and racketeers becoming acquitted of all charges in exchange for joining the Communist Party. In one political meeting he openly opposed the district secretary and this event marked all his subsequent life. In spring 1949 he was made to come to a post office under a false pretext and there attacked by StB agents, who pretended to be National Socialist partisans. He was taken to a forest and tied to a tree in front of a dug hole. Only a week after, the same people came for him again, this time officially. According to the materials from the Archives of Security Forces he was arrested on April 28, 1949 (he himself probably mistakenly speaks of April 14). The investigators charged him with armed attack on the above mentioned communist secretary. He was also charged with possession and dissemination of pamphlets, and with the intention to illegally leave the country. StB arrested his parents as well - he met them beaten in a staged meeting in front of the interrogation room - and probably also his brother. After a lengthy detention awaiting trial he was transported to custody in Prague-Pankrác. He was tried in the trial with the group Josef Vyhňák and co. - he has never seen some of the eight persons who were sentenced together with him. The principal trial of the State Court in Prague took place on September 27-28, 1949. Jaromír Stojan was sentenced to two years of heavy jail and the loss of civil rights for three years for the crime of plotting against the republic. The same court acquitted his father Jan Stojan. Several days after the trial, Jaromír Stojan was escorted to camp Vykmanov, where he was welcomed by a scene of a prisoner shot in an attempt at escape. Subsequently he got to camp Barbora, where he was going down the mine, but thanks to a friendly room leader he later got a less demanding position of a fitter. He managed to survive a cave-in, as well as a threat of leg amputation when he suffered frostbite during one of the many roll calls. His fellow prisoner roommates helped him again, and his leg was eventually saved. Half a year before his release he was offered to collaborate with StB, which carried a promise of an immediate return home. He didn’t succumb to the temptation. After his return from imprisonment he was surprisingly offered a position of a supervisor of a state-owned gardening company in Husinec. When he ascertained the real state of affairs, he discovered there was a financial shortfall in the company, which would have probably resulted in another sentence for him, and he turned the offer down. He eventually became employed by a construction company in Pilsen. In November 1951 he began a basic military service in the combat antiaircraft unit in České Budějovice. The commander often made use of his experience from the national defence and he repeatedly postponed Stojan’s transfer to the Auxiliary Technical Battalions (PTP). Eventually, Stojan was sent to PTP in Mimoň. He continued with the PTP after another transfer to Stříbro, from which he was a transferred to Slovakia to a military recreation facility in the Tatras Mountains after disagreements with the commander. The commander wanted to get rid of him, and he thus provided Stojan with half a year of a comfortable military service. Stojan completed his service with the PTP in Prague, where he participated on the construction of hotel Internacional. After his return in 1954 he moved to Havlíčkův Brod and began working in a local factory producing files. He was asked to join the Communist Party, but he obviously refused. In the evenings he studied a secondary industrial school and he began working as a standardizer, later as a tool setter and planner. He married in 1952, but the marriage didn’t last. With his second wife he raised two daughters. In 1968 he feared that the Soviets wouldn’t tolerate the “thawing” in Czechoslovakia, and he was not mistaken. Although he didn’t file for rehabilitation, in 1969 a rehabilitation proceeding began with his case. His troubles started after he truthfully testified in court about how he had been attacked by the StB agents. A high StB official demanded that he take back his testimony, which Stojan refused. His case was eventually investigated and this high ranking StB official then told him that his testimony had been true and that consequences had been made of it. In the period of Charter 77, Jaromír Stojan was asked to sign it as well, which he however refused, saying that even former communists were among the Charter’s supporters, and that the document itself did not fight the communist ideology, but defended human rights within this system. Freedom came for Jaromír Stojan in November 1989. He joined the Confederation of Political Prisoners, which made him a delegate in the civil safety commission; he also became actively involved in the local chapter in Havlíčkův Brod where he worked as a treasurer, and also as the chairman for the past five years. At the same time he is a member of the all-state committee of the Confederation. All his life he has been faithful to his credo: “Serve your homeland firmly, as a faithful guard, give your soul, give your heart, give her all you have.”