Danger is lurking behind the wires

Download image

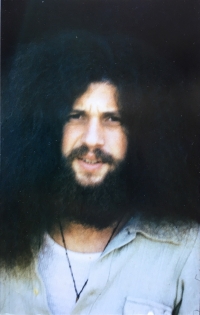

Jiří Středa was born on 13 April 1956 in Aš. He spent part of his childhood in the dark atmosphere of the western borderlands, where the cruel and distressing stories of the end the World War II were still lingered in the shadow of the daily presence of the Border Guard. In the late 1960s, the family moved to Olomouc. Jiří’s father, Jiří Středa, decided to emigrate to Canada after the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops. His son felt the same desire after meeting the Soviet occupiers. A meeting with people belonging to underground culture in the Olomouc pub U Musea turned out to be a crucial experience for him. Due to his poor cadre profile, he was not allowed to study secondary school, so he trained as a chemists´ shop-assistant. Because he wore his hair long and identified with the underground culture, the Olomouc police began to harass him and threaten him with imprisonment. Jiří therefore moved to Prague, where he immediately became involved in the artistic underground - he played in Miroslav Vodrážka’s “emotionalist” band. He also attended secret philosophical seminars of PhDr. Julius Tomin, whose family State Security forced to emigrate from Czechoslovakia as part of the „Asanace“ action. He himself experienced several interrogations by State Security. At the end of the 1970s, he married an Italian woman, Ornella Tomasi, but it was just make-belief marriage in order to obtain an emigration passport. This allowed him to travel between abroad and home, smuggling printed materials and messages that Pavel Tigrid was giving him in France. On his travels, Jiří Středa hitchhiked all over Europe. In the early 1980s, he signed Charter 77. He decided to leave Czechoslovakia for good in 1984. He was granted political asylum in Canada, where he met his father and where he had many jobs. In the late 1990s, he participated as a Charity worker in several humanitarian missions - in Ukraine, Macedonia and Chechnya. He returned to the Czech Republic permanently in 2004. His last job was as a prison guard in Olomouc, where he got into conflict with the prison management and only after protracted arguments he cleared his name and position. Jiří Středa is a holder of the 3rd (anti-communist) resistence certificate. At the time of the interview in 2022 he was living in Olomouc.