“Before 1989, if you walked the street and you heard Czech being spoken, you quickly looked around what’s going on. It was not only me who had that impression, but many other people have also confessed that they felt the same way when they heard someone speaking Czech.”

Download image

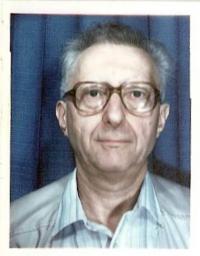

Long-time redactor and moderator of the Czech radio broadcast for the BBC Eduard Strouhal was born in 1928 in Prague in the Vinohrady neighbourhood. He spent a greater part of his childhood and youth in the Příbram region, where his parents owned a farm. In 1947 he graduated from a secondary school and began studying at the Law Faculty in Prague. In September 1948 together with his friend he crossed the border and got to Austria and then to Great Britain. There, he performed manual jobs; from 1952 he studied at the Belfast University. He completed his studies in 1956, afterward worked for seven years as an accountant for the Shell oil company. He worked in South America for 5 years, two years in Bolivia, two years in Argentina and one year in Columbia. After the termination of the Shell contract he returned to Britain, where he was offered a job by the BBC. From 1963 till his retirement in 1988 he worked for this British public broadcast service. He also contributed to the Czech broadcast as a redactor and moderator, specializing especially in economic news. At present he lives in London, and he visits the Czech Republic regularly once or twice a year