My granddad used his funeral savings to stop the communists from sending his daughter to prison

Download image

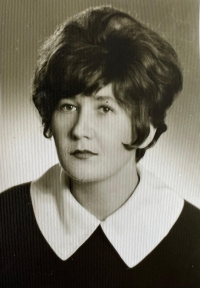

Vladimíra Sůvová was born as Vladimíra Špidlenová on July 25, 1940, in Vysoké nad Jizerou in the Krkonoše mountains. She grew up in her father’s farm in Příkrý village, where she started her primary education in the local village school. She then continued her education in Semily. Her parents were working the land as private farmers. After the coup in 1948, they got into trouble with the ascending communist power. They were labelled kulaks, that is members of the land-owning class of village exploiters. They found it impossible to meet the required quota of produce to be handed over. For not submitting the required amount of milk, they were facing a high fine, or even imprisonment. Vladimíra Sůvová’s mother was prepared to go into prison instead of her sick father. In the end, her father paid the fine using the money he had saved up for his own funeral. The parents eventually gave in to the pressure of the authorities and joined the local collective farm. Thanks to lucky coincidence, Vladimíra Sůvová graduated from a teacher-training secondary school, in those days dubbed an “eleven-year school”. After graduation, though, because of her unfavourable class origin, she had to return to manual farming work. At the age of twenty, she married her former classmate who had in the meantime become a professional soldier. Thanks to the change of her last name and the fact that her husband was of working-class origin, she was finally able to leave the farming labour. The newlyweds received a military flat in Zákupy in the vicinity of Česká lípa. A baby-daughter was born. Vladimíra Sůvová started teaching Czech and Russian at a primary school. While working, she graduated from the Institute of Pedagogy in Liberec. Following the year 1968, her husband was posted away to Hradec Králové, where Vladimíra Sůvová started teaching at the Pavlík Morozov Primary School. She worked there for seven years. The combination of the school’s ambitious, politically driven headmaster, the onset of normalisation and bad relations with people ruined her health. Her husband resigned from his military post in Hradec Králové and together they moved to Semily. She continued teaching until well into her late sixties, first in Jesenné and later in Semily. She published her memoir in which she recounts her family farming history and the hard times they experienced in the 1950s in her book “Čím jsou lidé živi” / “What People Live On”. In her next book, “Ave Maria”, she partly draws on her experience from the Pavlík Morozov Primary School. The book is partly dedicated to the issues of special-needs children’s parents. In 2023, a widowed Vladimíra Sůvová was living in Semily and she was still keenly interested in public affairs.