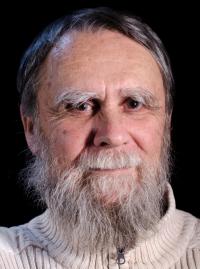

I signed Charter 77 and the Church considered me a saboteur

Download image

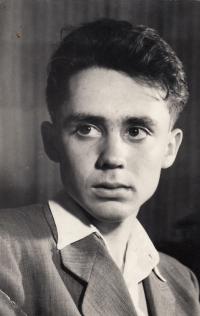

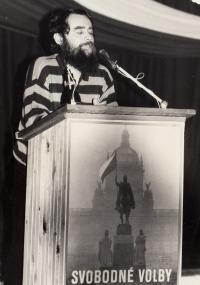

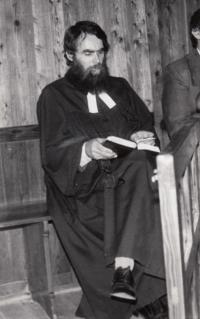

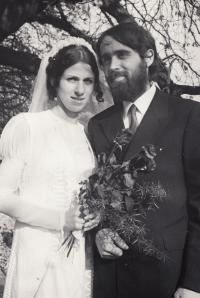

Vojen Syrovátka was born on March 8, 1940 in Prague. His father Václav Syrovátka was an active member of the anti-Nazi resistance and after 1948 joined campaigns against the communist regime. He was sentenced for these activities and spent fourteen years as a political prisoner in labour camps and prisons. The teenage Vojen felt acutely the absence of the father in the family. He found help in the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren in Prague-Dejvice, which he started attending at sixteen. It was here he found friends and developed an interest in religion. He trained as an electro engineer. During work he studied a grammar school and then was accepted to the Evangelical Theological Faculty, Charles University. It cost him much effort since his employer refused, for four years, to provide him, the son of a political prisoner, with the recommendation, a necessary condition for being accepted at the university during socialism. In the seventies he worked as a parson in Rumburk and other districts of the former Sudenteland. He signed Charter 77 and met the dissidents. He was often interrogated by the Secret Police. After 1989 he co-founded the Civic Forum in Rumburk. He served in the Diakonia’s board and contributed to the building of an old people’s home in Dvůr Králové. He has become one of the most respected members of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren. Since 2010 he has served as a parson in Vilémov.