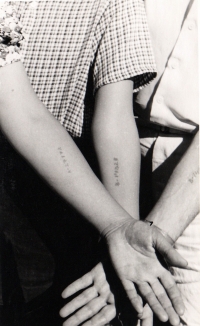

They tattooed us. And that meant hope for us

Download image

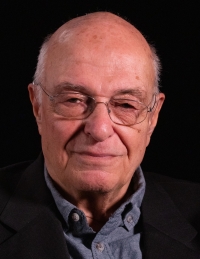

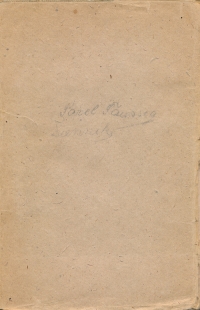

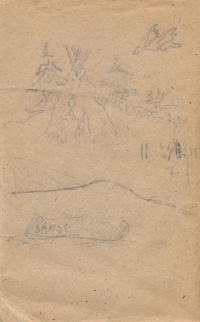

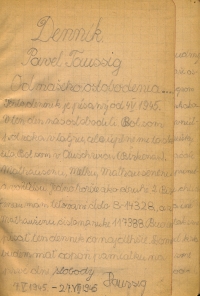

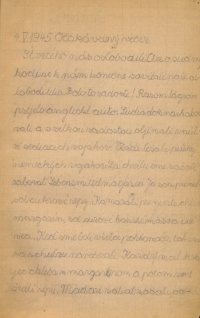

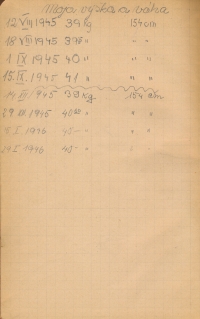

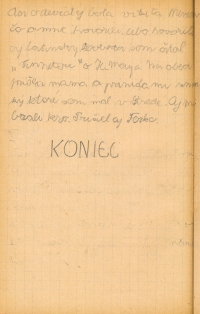

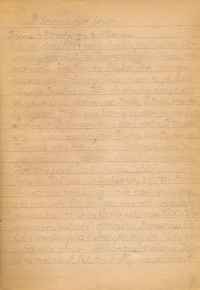

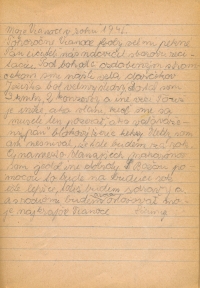

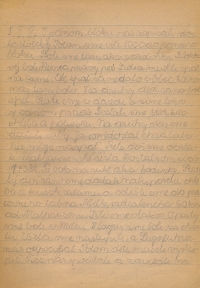

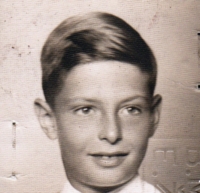

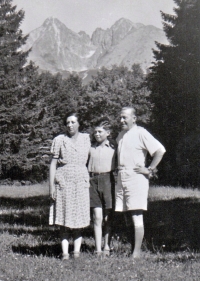

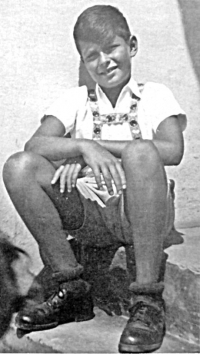

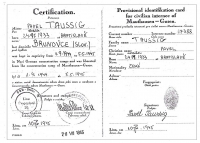

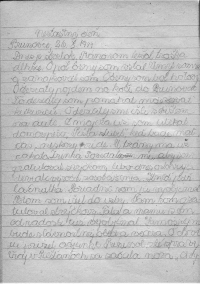

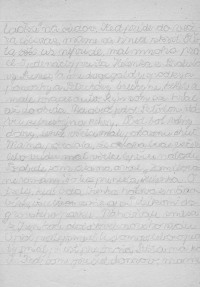

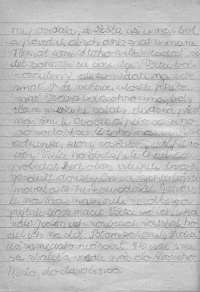

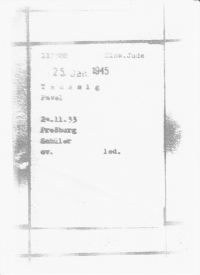

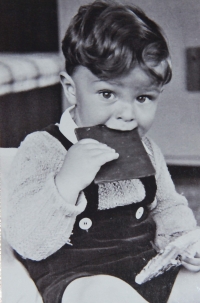

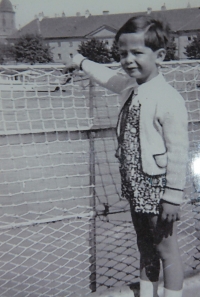

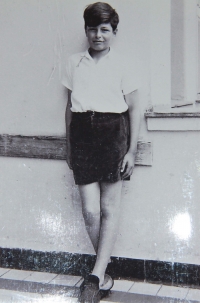

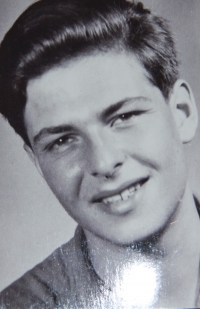

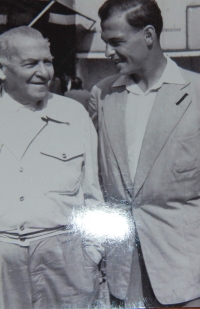

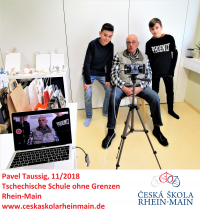

Pavel Taussig was born on November 24, 1933 in Bratislava to a Jewish family as the only son. His father Artur Taussig ran the company, his mother Jolana was a housewife. The family was Jewish, but fully assimilated. Pavel Taussig attended a Slovak school and later a grammar school. After the establishment of the Slovak state and the introduction of anti-Jewish measures, the father acquired the status of an economically significant Jew, which to some extent protected the family from deportation. In the summer of 1944, the Taussigs moved from Bratislava to the village of Brunovce. There, at the end of October 1944, they were arrested by guards, taken to a camp in Sered, from where they were deported to Auschwitz in early November. Pavel Taussig lived first with his father, then in a block with similarly old boys. In mid-January 1945, together with other prisoners, he accomplished the evacuation of the Auschwitz camp, the so-called death march. At the end of January, he got to the Mauthausen camp, later he was transferred to the Melk camp. He was liberated on May 4, 1945 in the Gunskirchen camp. After basic convalescence and treatment in Hörsching and Linz, he arrived in Bratislava in July, where he met both parents - his father was liberated in Auschwitz in January 1945 and his mother returned from the Lippstadt camp. Pavel Taussig was treated for tuberculosis for a year in a sanatorium in the High Tatras, and re-entered the school in the autumn of 1946. He later studied librarianship and Slovak at the University of Bratislava. He was employed by the Slovak Publishing House of Beautiful Literature as a librarian, later as the head of the promotional department, then he was the editor of the satirical magazine Roháč. In August 1968 he emigrated to Germany, where he worked in the editorial offices of the satirical magazines Pardon and Titanic, as well as in the daily Ärzte Zeitung. He and his wife raised two sons. In 1985, his collection of satirical short stories, The Unique Saint, was published in Toronto, Canada, and in 1987, the book Dumb, But Ours was published there. In 2012, he published the novel Hana in Budmerice. In 2018, his book The Boy Who Survived the Death March... and I Didn’t Die was published, which was based on diary entries that Pavel Taussig kept shortly after his liberation during his convalescence in the summer of 1945.