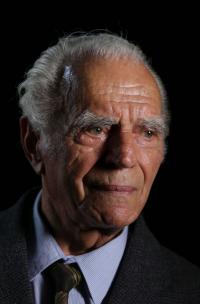

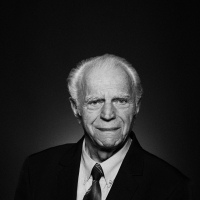

I don’t even think of a revenge

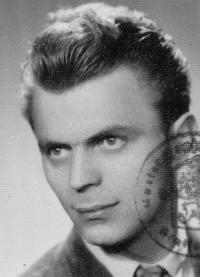

Anton Tomík was born on 2 June 1932 in Skalica, a city on the Slovak-Czech border, into an agrarian family. He grew up at times of crisis and penury and started attending school at the era of the fascist Slovak State. For a long time his family wasn’t directly affected by the war. However, in its late years, allied and Russian shelling had intensified and eventually also damaged the family house. Following the 1948 communist putsch, Anton’s family was subject to forced collectivization. Anton studied mechanical engineering in Bratislava and dreamt of becoming a pilot. During a summer trip to the Slovak mountains in 1951 he was arrested with several friends and falsely accused of subversive activities. To make things worse, the investigators found weapons in his dorms which he and his colleagues discovered randomly in a ditch. Anton was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for high treason. He was transferred to a uranium mine in the Jáchymov region where he operated carts transporting slag. In 1955 he and his nine inmates dug out a tunnel and escaped from the camp. After two days he was apprehended and wounded in a shootout. He received an additional two-year sentence but was moved back to Leopoldov where he could receive family visits and where he got a good job in an electrics workshop. He wasn’t subject to the presidential amnesty in 1960 but successfully applied for a conditional release only a few months later. Soon after release he got married and ever since worked in engineering. After more than sixty years he had received his high school graduation certificate in 2014.