I was collecting antiques and at one point I threw away everything that was German

Download image

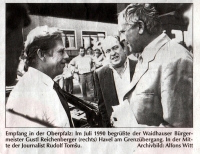

Rudolf Tomšů was born on February 7 1941, in Pilsen. In 1946 he moved with his parents and sister to Tachov in the West Bohemian border region. At that time, the town struggled to recover from the events that had befallen it during the Second World War. Much of Tachov was severely damaged by the American bombing, and dozens of houses were left in ruins. In 1946, the vast majority of Tachov’s original German inhabitants resided in an assembly camp where people awaited deportation to Germany. The empty houses did not escape the wave of looting, and only then did the new inhabitants begin to move in. They often came also from distant countries and found it difficult to relate to their new home. Rudolf Tomšů recalls playing with other children in the destroyed houses; he also remembers his father crying after he returned from a visit to the collection camp and the two hungry German older men whom his father brought from there and who stayed with them for several days. Life in the following years was marked by the building of the Iron Curtain. Many villages in the area were razed to the ground by the Czechoslovak army. In the first half of the 1960s, the witness was offered a job at the district newspaper and, at the same time, became the editor of the local radio station over the wire. When the occupying Soviet army arrived in Tachov in 1968, he tried to report objectively on the events in the newspaper and the radio. In 1969, he resigned from the Communist Party in protest against the Soviet invasion and left the editorial office of the Tachovska Jiskra. During the period of normalisation, he worked as a labourer and, at the same time, started making amateur films. In 1989, he became involved in the Civic Forum in Tachov, but he did not accept the offer to run for mayor. His big personal issue was the expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia after 1945. He wrote many articles and lectured in Bohemia and Germany. He was married twice and is a father of two children. At the time of the interview (2019), he lived in Tachov.