Why should I appeal? It was a perfectly pre-planned play

Download image

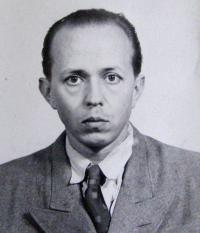

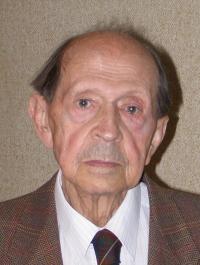

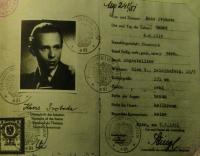

Miloslav Trubáček was born in 1916 in Prague. After the Second World War, he was emploied by the Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs and completed his law studies. In 1946, he served as a second secretary at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Moscow, where he refused to join the Czechoslovak Communist Party and to collaborate with NKVD. In 1949, therefore, he had to return to Prague to the ministry, where a “personnel exchange” was in progress. Trubáček was fired, however, the head of the Department of Reparations hired him, which made it possible for him to stay at the ministry until 1953. In that year, he was arrested while attempting to emigrate to Austria, at least partially provoked by secret police. In 1954, a court condemned him for 16 years for alleged espionage and high treason. In 1956, a revision of Trubáček’s sentence started but it was interrupted by the Hungarian revolution. As a result, he remained in prison until a presidential amnesty in 1960. In 1971, he was partially rehabilited. After his release, State Police considered whether to send him to the West as an agent but such a plan was finally rejected. So it was only due to his own abilities that he managed to get from the position of laborer in the Prague Transport Company to the function of a lawyer authorised by the Foreign Trade Minister to liquidate a stock company.