The witchhunt for rock bands was why I left the country

Download image

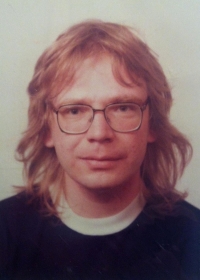

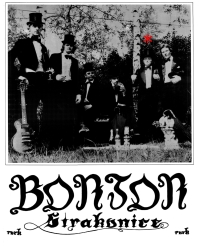

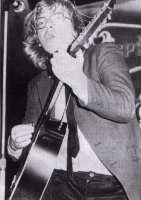

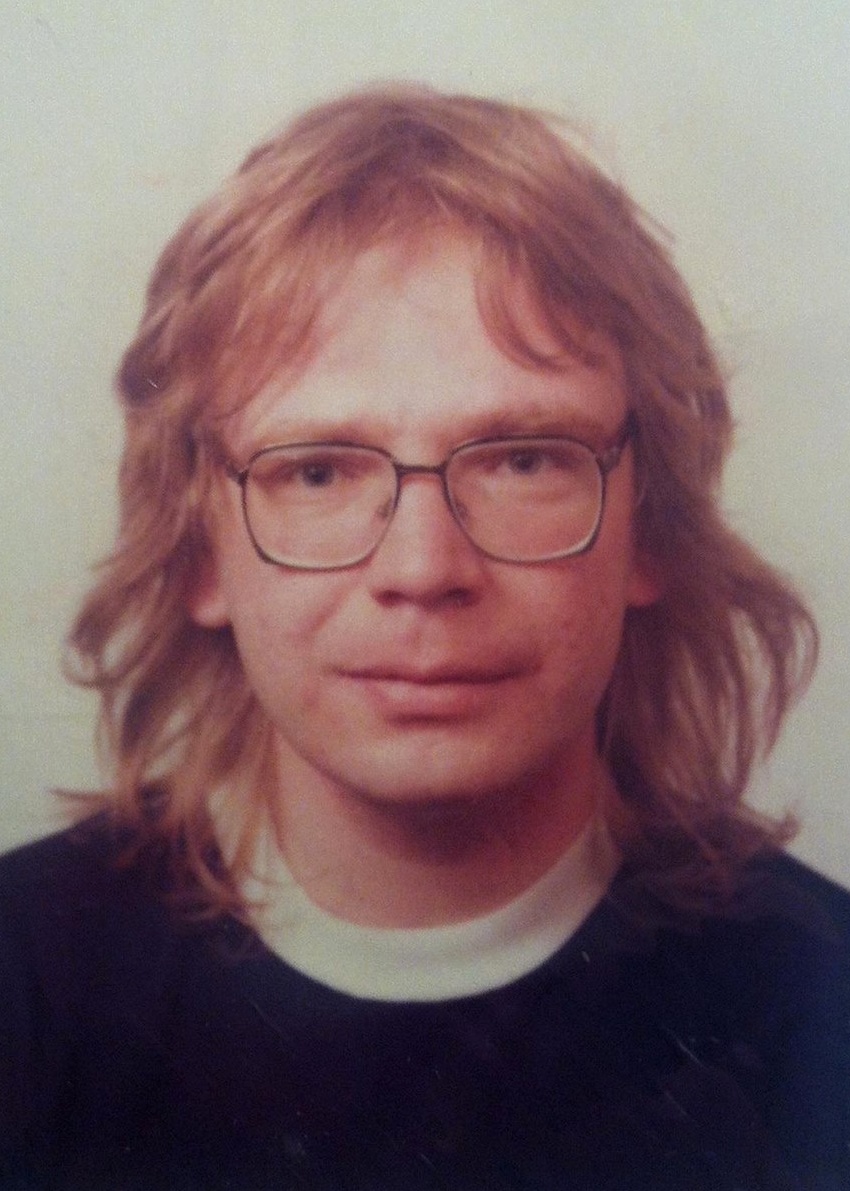

Jan Tyl was in Mariánské Lázně born on 30 July 1956 and lived there until he was fifteen. He studied at a secondary technical school in Volyně, South Bohemia, worked as a labourer at a sawmill in Nepomuk near Strakonice and began part-time studies at the University of Economics but did not finish due to emigration. His grandfather Emil Tyl ran a mill until 1948 and produced electricity for the West Bohemian region, while his mother, Vlasta Tylová, came from a family of farmers. Both families lost their property after the communist coup in 1948. In the 1960s and 1970s, Jan Tyl listened to rock music and played in punk rock bands with his friends at dance parties. In 1974, concert bans began to come in, so he decided to emigrate to Canada in 1982. He left Czechoslovakia with wife Jana and son David via Yugoslavia and Austria in 1983. They were granted political asylum in Austria and left for Edmonton, Canada in October 1983. Jan Tyl completed his university education in Canada and passed his auditor exams in 1992. Following divorce in 1993, Jan Tyl returned to the Czech Republic for four years, developing the local PriceWaterhouse office. After four years, he moved to the management of Grant Thornton’s Czech office. Until 2014, he held various jobs abroad - he founded an audit chamber in Kosovo, later worked for the World Bank in Vienna and visited the Czech Republic where he has lived permanently since 2014. Since 2013, he has been involved in tourism, CBD products and restaurant business, and today he helps non-profits Amélie and Hyb4City. He lives permanently in Černošice in the Central Bohemian Region.