The older prisoners laughed at me that I was taken right off the rocking horse

Download image

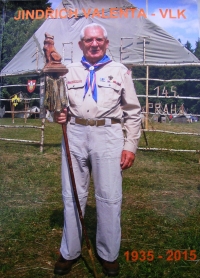

Jindřich Valenta was born on January 7, 1935 in Prague, Bohdalec. Soon afterwards, the family moved to Žižkov, where they lived through the Second World War. Jindřich, who was ten years old at the end of the war, joined the re-established 36th Scout Troop in September 1945, where he acquired the nickname Vlk. A few years after the official inclusion of all youth organizations under the Czechoslovak Youth Union and the demise of Junák, he joined the illegal 34th Ostříž Centre organized by Oldřich Rottenborn. At that time, a group of scouts printed and distributed anti-state leaflets or organized small sabotage actions. After one of them, some of the members were arrested and sentenced to minor prison terms in the Jáchymov camps. Jindřich received a suspended sentence at that time and together with other scouts formed the so-called Štáb sedmi (Staff of Seven). This was a group that continued its anti-state activities from 1952 to 1954. In the middle of this period, Jindřich was recruited by State Security for cooperation. He informed the other members of the troop of this fact right after the first meeting and together they tried to give them false information about their activities. The group was in possession of firearms at the time, which also became the main motive for the trial begun after the re-arrest in October 1954. In it, Jindřich received a seven-year sentence and served three years of it in the Rovnost camp in Jáchymov. He spent the next two years in Opava prison, where he joined the failed revolt. He was released in 1960 from Valdice prison, where he spent his sixth and final year behind bars. Shortly afterwards he was called up for military service with the so-called Technical Battalions. He subsequently worked as a mechanic of washing machines and centrifuges for most of his active life. After 1989, he became deputy head of the 34th Ostříž Scout Centre, which no longer had to operate underground.