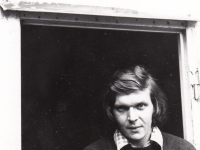

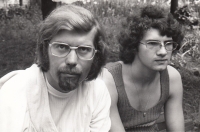

I owe everything that is good in me to my grandmother

Download image

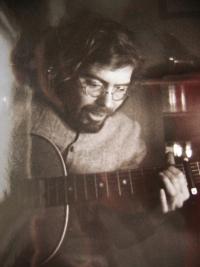

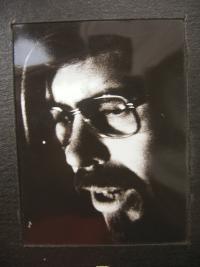

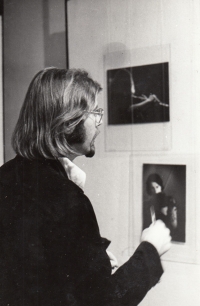

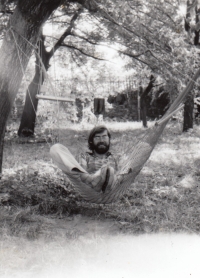

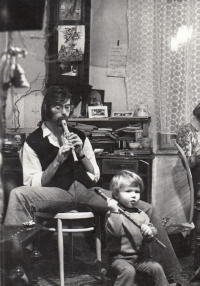

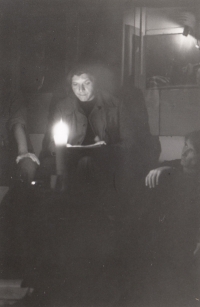

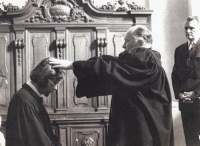

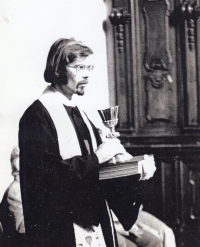

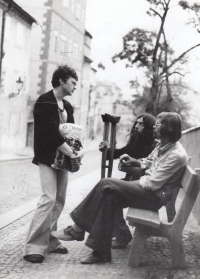

Rostislav Valušek was born on 18 June 1946 in Olomouc. Due to the communist regime coming to power in 1948, his father Augustin lost his thriving shoemaking workshop. Rostislav was also not allowed to study at his dream art school. Instead, he trained as a locksmith. After the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968 and the subsequent self-immolation of Jan Palach, he decided to emigrate, but he returned from abroad three months later out of love for his grandmother Františka. In Prague, despite his occasional political disgust with the emerging normalisation, he managed to graduate from the Hussite Theological Faculty of Charles University. During this period he made important contacts with the Prague dissent and also created his first samizdat - a collection of texts by Ladislav Klíma, which were given to him by the poet and philosopher Egon Bondy. He continued his samizdat activities after his return to Moravia, where, after meeting Petr Mikeš, he became involved in the production of the samizdat edition Texts of Friends. After he was mentioned in a television speech in 1977 by the then First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Slovakia, Vasil Biľak, Rostislav Valušek came to the attention of State Security, which offered him cooperation and promised him a rich parsonage and the publication of his poetry in return. Rostislav Valušek refused, and not only because of this he was unable to exercise his priestly profession until the Velvet Revolution in 1989 - he worked in many jobs, the longest of which was as a pumpman living in a construction trailer. During the revolutionary events of 1989, he participated in a meeting in Olomouc’s Upper Square at the Holy Trinity Column. He entered the priestly vocation in 1990 and was still in it at the time of the interview in 2023. He and his wife Marcela raised two children, Anna and Jan. In 2023, Rostislav Valušek was living in his family home in Olomouc.