When the occupiers came, the militiamen were with us. The next year it was the other way round and they were with the occupiers.

Download image

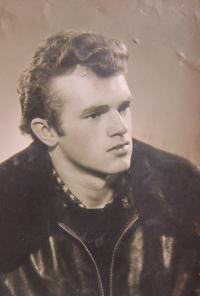

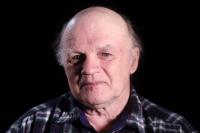

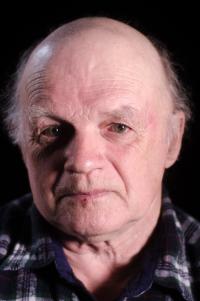

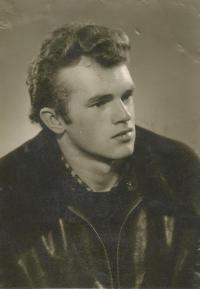

Miroslav Vaněk was born on August 1, 1946, in Moravský Beroun. However, he spent his childhood in Bystřice pod Hostýnem. There he spent a lot of time on the farmstead of his grandparents who, during the collectivization of the countryside, steadfastly refused to join the collective farm cooperation (JZD). Thus the local Communists sought to destroy them and nationalized their family business. The whole family found itself on the index of inconvenient persons. Therefore, when Miroslav Vaněk finished elementary school, he had to sign up for the Dukla Mining School in Havířov. Among other things, this was where he, on August 21, 1968 in the course of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops, witnessed four Soviet tanks that surrounded the drilling rigs and threatened to blow them up. The miners then immediately went on strike to protect their colleagues located underground. On the first anniversary of the occupation, he participated in a demonstration in the city of Havířov, which was brutally suppressed by the police. Eleven years of work in the Mine Dukla left a mark on him in the form of broken health. To this day, he often recalls images of the fatalities of his mining friends. For all of his life, he made no secret of his opposition to the communist regime, and when he heard about the crackdown on the demonstrators on National Avenue on Nov. 17, 1989, he went to Prague himself to attend these demonstrations.