Music is a beautiful thing and without it life is terribly empty

Download image

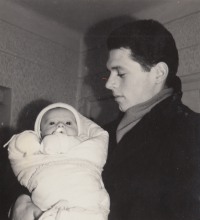

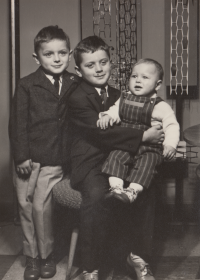

Josef Varmuža was born on 15 October 1963 in Kyjov as the eldest of six siblings, these being: Pavel, Jiří, Petr, Kateřina and Hana. He spent his childhood in Svatobořice-Mistřín, where his parents raised him to follow the Christian faith. For example he served as an acolyte in the local church. In the year 1964 his father Josef co-founded Varmuža’s Cymbal Music, which his son joined in the year 1976 at fifteen years old. Since the year 1986 Varmuža’s Cymbal Music has been a purely family group. In the second half of the 80s the band faced constant pressure to join the local house of culture, which the family didn’t want, as it was concerned with constant oversight and the relative loss of freedom. This pressure stopped after three years in 1988 as a result of the ruling of a District National Committee of Hodonín. In the year 1989 Josef Varmuža participated in the demonstrations in Prague that were part of the Velvet Revolution and was a witness of the destruction of a statue of Lenin in Kyjov in the year 1990. Currently (the year 2022) he still devotes himself to folklore.