To find your own way and feel that you’re not a puppet

Download image

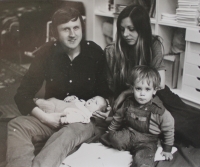

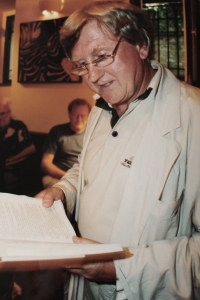

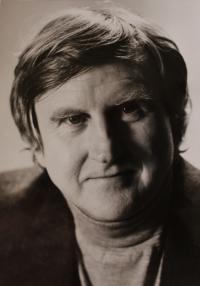

Vlastimil Venclík, a Czech playwright, screenwriter, director, and actor, was born on 1 September 1942 in Kyje near Prague. After studying at grammar school and the Secondary School of Society and Law, he was accepted to the Film Academy in Prague in 1966. His reaction to the Soviet occupation in August 1968 and the ensuing normalisation was to shoot the student film Nezvaný host (The Uninvited Guest) in April 1969, starring Pavel Landovský. The film was seen as an attack on the Communist regime and was confiscated by State Security for a whole twenty-one years. Its author was subsequently expelled from the Film Academy and earned his living for a number of years at the District National Health Institute in Prague as a sick-leave inspector. At the time he began to break through as a playwright, screenwriter, and occasional actor. After 1989 he directed some his own scripts and theatre plays. One of his best-known television works is the documentary series Zprávy o stavu společnosti (Reports on the State of Society). After 1989 he co-authored the project by CET 21, which received a license for independent television broadcasting. In 1993 he had to come to terms with the violent death of his son, after which he established the Filip Venclík Foundation. In 2018 he was elected into the Czech Television Council; he lives in Prague 2.