The Communists drove my grandparents into a barn, took away my father’s butcher shop, and I wasn’t supposed to graduate

Download image

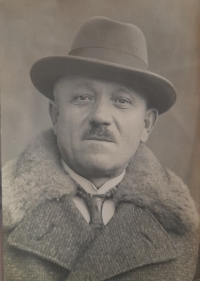

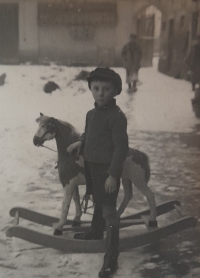

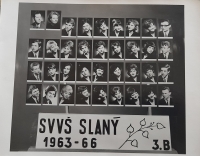

Marie Vladyková, née Černá, was born on 19 July 1948 in Zlonice into the family of Čeněk Černý and Marie, née Hornická. Her maternal relatives have roots in Zlonice that are said to go back 400 years. Her father and grandfather were local butchers, and her maternal grandparents had a farm there. Marie grew up with her brother, two years older than her, Čeňek. In 1953, the communists ruthlessly expropriated her grandparents’ farm and evicted them from Zlonice to two small rooms of an outbuilding in Blahotice, which had served as pigsties until then. A little later, they took away the butcher’s shop from her parents, which they had in their own house on the square. Her father was supposed to go to work in the mines, but he fought to stay and sell in the shop that was taken over by the consumer cooperative Pramen and then Jednota. His wife continued to work with him in the shop but did not receive a salary. Both Marie and her brother Čeněk graduated from primary school with honors. Čeněk was not allowed to apply to a high school and was supposed to become a bricklayer, but thanks to the intervention of a friend, he got an apprenticeship as an electrician, and later, while working, he graduated from secondary industrial school. Thanks to the best results in the entrance exams, Marie got into high school, but she was not supposed to graduate. She got disqualified from the mathematics examination without any reason. She graduated on appeal after the reexamination. Because of her cadre materials, they would not employ her anywhere except on a state farm, where she was offered a job in the fields. Thanks to an acquaintance, she found employment in an office in a construction company in Zlonice, which did not please the communists from the national committee, and they sought her dismissal. Over the years, Marie graduated from a secondary school of economics while working as an accountant. She tells how she lived through the main events of 1968 in Zlonice. In the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, she lived with her husband in Hovorčovice. In 1995, she moved to her family home in Zlonice, where she continued to live in 2023.