We used to call the new MB the Skoda 1000 of Small Pains

Download image

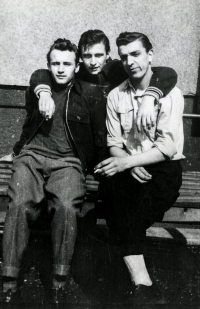

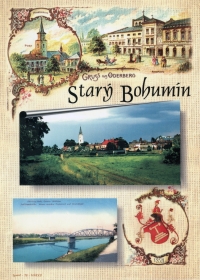

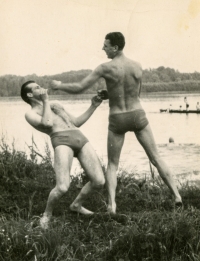

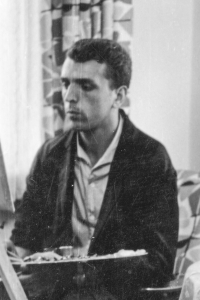

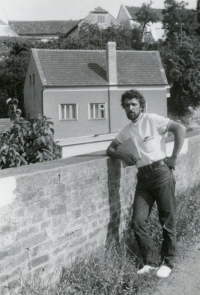

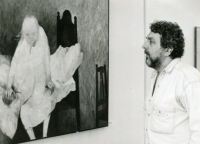

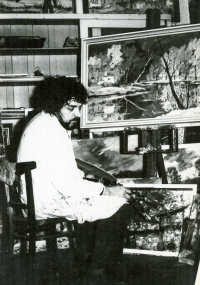

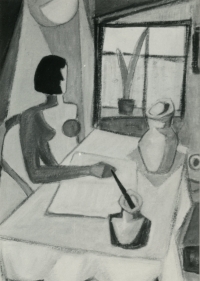

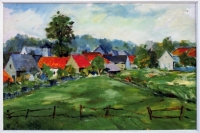

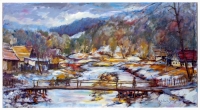

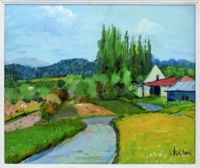

On 12 October 1937, Jan and Terezia Vlk’s second-born son Vladimír was born in Únanov. At the end of World War II, a single bomb fell in the village. After the war, the family moved to the house of the displaced Germans in Znojmo. The mother worked for a farmer who beat her for picking up the leftovers after the harvest. After elementary school, Vladimír Vlk went to Bohumín with the prospect of high earnings to a metallurgical apprenticeship, where he experienced the boom of heavy industry in Karviná. He worked in the local ironworks as a foundryman together with Poles. He was not allowed to discuss politics with them, as he was threatened with dismissal. During the war, he joined a battalion in Jinonice to protect the air section to the west. After the war, he considered moving to Vítkovice Ironworks, but a fatal accident happened there. He stayed in Bohumín, studied at the metallurgical industrial school and devoted himself to painting. In 1962, he moved to Mladá Boleslav to follow his love. He worked in the local automobile factories as a foreman in the aluminium foundry. There he felt restricted because he was not in the Communist Party. In 1968 he disagreed with the Soviet invasion and painted anti-state posters. He continued to paint actively, founding the Arsclub and later the art group Vlna. He continued to paint in 2023, when this interview was conducted in Dobrovice, Mladá Boleslav region.