“We wanted to make the comrades realize that it might turn against them.”

Download image

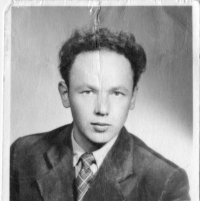

Stanislav Vobejda was born November 5, 1930 in Proseč. After completing higher elementary school in Slatiňany he went to study at the Salesian grammar school in Fryšták in Moravia for one year. After his return home, he began working as a forester trainee in Posekanec. In 1949 he joined an anti-communist group which was founded in Proseč by his friend Josef Odehnal. Stanislav Vobejda had firearms as his hobby, and he was even able to obtain an automatic firearm for the group. The gun was never used, because the group disbanded soon after. Several people who had not been involved at all were however arrested due to the hiding of the weapon. After one action in Proseč, when the group fired a gun once into a window of the Party official Čoudek, two of its members fled the country and the automatic gun was subsequently passed over to other persons and concealed. In spring 1949 Vobejda decided to escape as well, but he didn’t manage to cross the borderline in western Bohemia and he was arrested. For an illegal attempt to leave the country he was sentenced in Cheb to one year of imprisonment and a fine to 10 000 Czech Crowns. The group meanwhile continued in conducting intimidatory activities in their hometown. Josef Lněnička became their leader, but only for a short time, because in September 1949 the State Police found out about the group and arrested its members. Investigation brought the StB to Cheb, where Vobejda was imprisoned for his attempt to leave the country. He was transported to Pardubice and investigated in relation to the activities of Lněnička and his friends. The motives behind the shooting into the official Čoudek’s window in spring 1949 were revealed as well. A large-scale trial with 19 participants was held in October 1950; most of the accused had only minor involvement in the group, or none at all. The individuals in court knew each other because they came from the same small village, but they mostly saw each other for the first time when they were brought to the courtroom. Stanislav Vobejda was sentenced to 19 years of imprisonment for high treason. The months in solitary confinement in Pardubice and in custody in Chrudim were counted into his sentence and after the trial he served his sentence in Pilsen-Bory, Písek, and in the uranium mine labour camp Vojna near Příbram. He was released in 1956.