The more one is old, the more he has to work on himself so that he doesn’t turn into a grumpy old man.

Download image

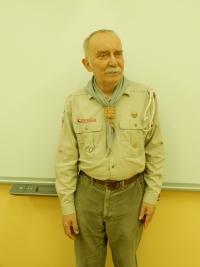

Antonín Wagner also known as Seagull has been an active scout in Horní Počernice ever since being 18 years old. He was born in Horní Počernice during wartime, on 23rd August 1944. His mother was born in Vienna and then moved to Znojmo and then to Prague, where she started a ladies’ tailor shop. At the height of its boom in 1948, she was teaching six young dressmakers. Antonín’s father was born in Prague and worked in a shop until the war. After 1945, he started working in the Charity organization, from where he saw how the Communists crashed the Catholic Church. Thanks to the experiences of his parents, Antonín was aware of the political situation since being a child so that he understood he couldn’t talk about some things in front of certain people.He had troubles in school since being very young also because of his Catholic background. After finishing the basic school, he was “not recommended” for any further education. Only because of a lucky coincidence did he get a permit to visit the ninth grade. As the school had also a high school program, he could “illegally” finish his studies as no control found out about him. His sister was also persecuted because of her religious beliefs. The dean of the Mathematical-Physical Faculty explicitly wrote that the refusal of her acceptance was motivated by her Catholicism.Mr. Wagner started to engage as a scout in the second half of the 1960s. Even though he wasn’t raised as one, he and his friends were inspired by the attitude of the “1945 scouts”. They had a big natural authority and respect, because even though they suffered terribly in the 1950s, they never complained to anyone. In Horní Počernice, he knew two scouts that were sentenced to fourteen years in prison at the age of eighteen by the Communist regime right in 1948. All they did was spreading anti-regime leaflets.In 1989, Antonín Wagner organized several important events. As a member of the organizational committee, he arranged a mass tour to Rome where Agnes of Bohemia was about to be canonized. There, most of them slept in a cinema auditorium even though some paid more to be in a hotel. Some women stayed in a monastery. Being appreciated for his skills, he later helped with the organization of all three visits of the Holy Father John Paul II to Prague. His duty of a member of the crisis and international staff was to make sure that everything happened as it should have.Despite helping with the realization of these great events, he feels best when organizing camps and everyday activities for young scouts. He works with them on many projects in Horní Počernice. He hopes that the work with the young will help him avoid being a “grumpy old man”.