Prague’s Černý Most housing estate stands on land taken from them by the communists

Download image

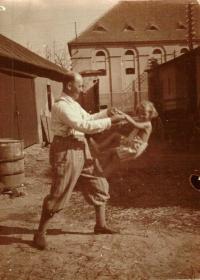

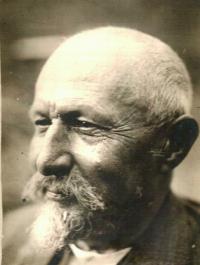

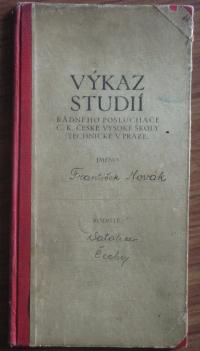

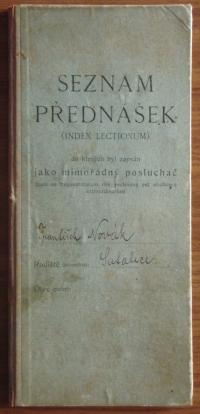

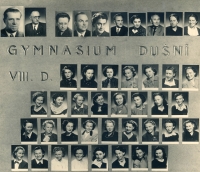

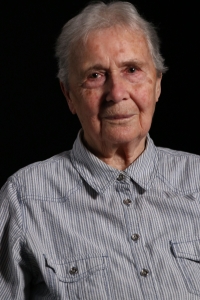

Eva Warausová was born on 29 June 1932 as the younger daughter of the landowner František Novák. He farmed 50 hectares of land between the villages of Chvaly, Svépravice and Horní Počernice, on the eastern outskirts of Prague. His parents also owned a chateau in Vinařice near Mladá Boleslav, together with 80 hectares of fields, meadows and forests. From 1942 Eva studied at the eight-year Charlotta G. Masaryk´s Real Gymnasium. In March 1945, her father, sister and aunt were wounded in an Allied air raid on the Kbely airfield. In 1947, the so-called millionaire’s tax was imposed on her father, after which he was left permanently in debt. When his farm machinery was confiscated after the Communist takeover and compulsory levies were set at a liquidation rate, he preferred to hand over the farm to the state. His parents had to move out of their house. Eva married Pavel Waraus in 1951 and moved with him to Sokolov, where her husband found work in the mines. Later they moved to Prague and both supplemented their education while working. Eva then worked at the Central Laboratories at the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University in Prague until her retirement in 1990. After the Velvet Revolution, the family restituted the wine chateau and land, but sister Věra was no longer able to start farming, so they rented the fields and sold the chateau. Only a small part of the farm in Chvaly was returned to them - the buildings were completely destroyed and the land was used for industrial enterprises and was used for the construction of the Černý Most housing estate. No one from the traditional farming family is farming today, but Eva’s descendants live on the site of the original Chvaly farms.