As a student, he protested about the darkness in university dormitories, only to get hit with a baton

Download image

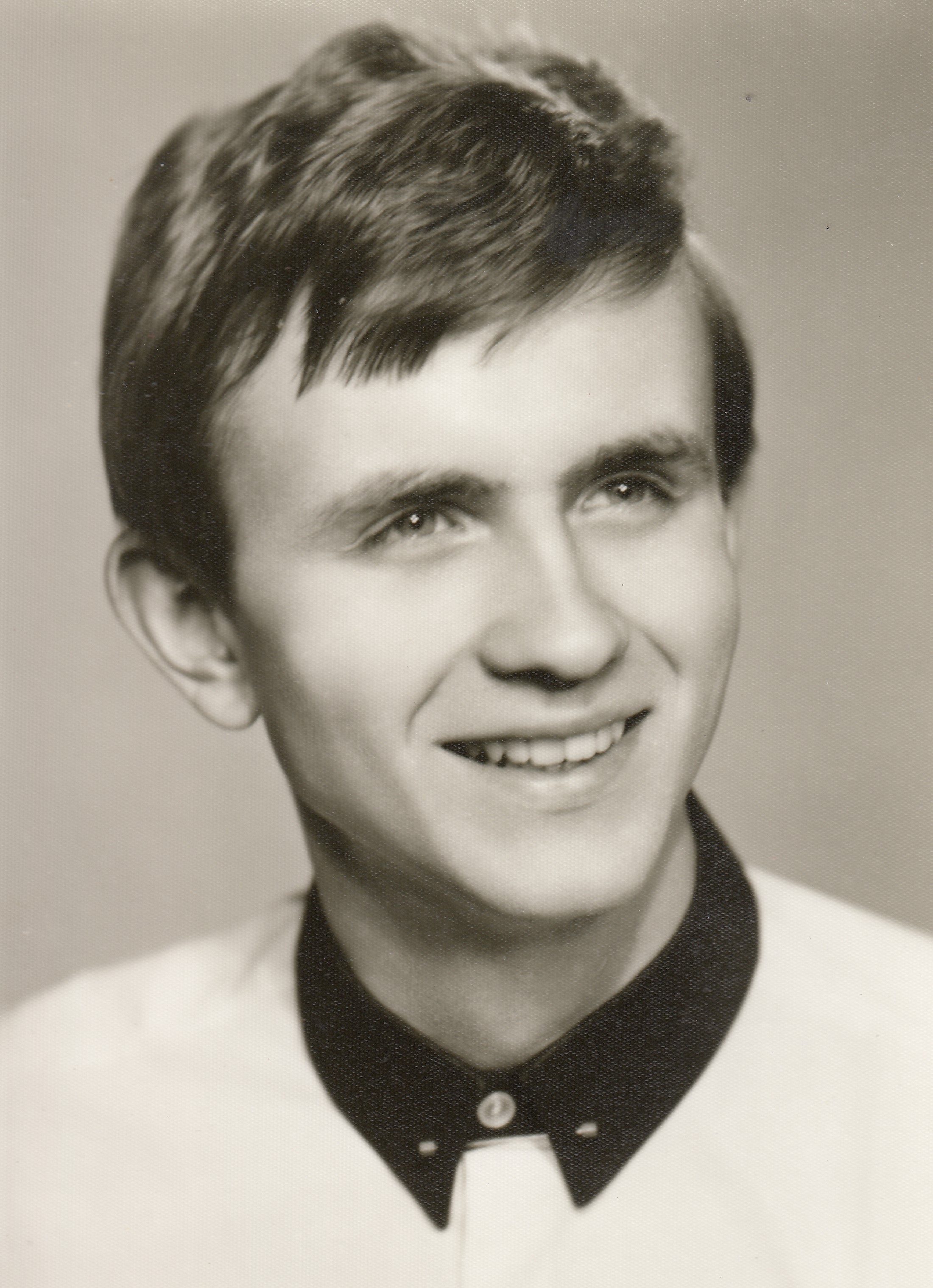

Viktor Weilguny was born on 26 December 1946 in Cheb. His father served in the Wehrmacht during World War II, first on the Eastern Front, then in the West. Together with other Czechs, they defected to the English. His father then worked as a driver for the UNRRA and made it all the way to Prague. His first wife died on 8 May 1945 during the Soviet air raid on Teplice. Father remarried after the war and worked as a shoe merchant, first in Cheb and then in Karlovy Vary, where the family lived in the Baťa department store. As a student of the Czech Technical University, the witness participated in the protest at Strahov dormitories on 31 October 1967. In August 1968, despite the occupation, he decided to return from his stay in West Germany. After graduation, he worked in the construction industry and also as a teacher at a secondary industrial school. In 2023, he was living in Karlovy Vary and still earned his living as a designer and forensic expert.