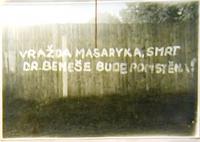

Death to Communism!

Download image

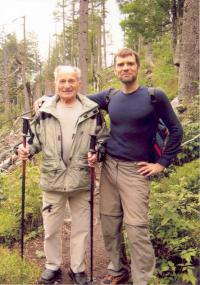

František Wiendl was born on December 31, 1923, in Klatovy. His father, František Wiendl senior, was a carpenter. He was imprisoned by the Russians in the time of the First World War and he witnessed the October revolution of 1917 in Russia. This first-hand experience deeply influenced the stance of the family towards Communism. During WWII, the father and the son got involved in the resistance activities against the Nazi occupants. The father of František was a member of the resistance organization ÚVOD. Unlike his friends, he was lucky and wasn’t revealed and arreseted by the Germans. After the Germans burned down the village of Lidice, he founded his own resistance organization and named it Lidice to honor the memory of the village. His son was also involved in the organization. The bulk of the activities of the organization consisted of financial contributions to the families of those who had been arrested by the Nazis. They also distributed leaflets and gathered weapons and material that they wanted to use in the event of an uprising. The group later joined the greater organization Niva that received its instructions from the oversea Council of the tree - a channel to maintain contact with the abroad. The uprising broke out by the very end of the war in May 1945. The resistance fighters disarmed the German soldiers in the city even before the advent of the American army. Mr. Wiendl became a mason and he studied the technical college of construction in the time of the Protectorate. After the war (1945-1947), he did his basic military service and he attended a school for reserve officers. The rise of the Communists to power and the death of Jan Masaryk led the Wiendl family and their friends from the war to join the so-called “third resistance” against the Communists. At first, they focused mainly on writing anti-Communist slogans and distributing leaflets. Since April 1949, they were also guiding fugitives across the border and they were in touch with agent-walker Alois Suttý. The group was broken up in successive steps. At first, František Wiendl and a fellow associate were betrayed and arrested in November 1949. The rest of the group, including František Wiendl senior and agent Suttý, was arrested in the spring of 1950. The trial was held in December 1950. Agent Suttý was sentenced to death and executed, Mr. Wiendl senior was sentenced to 25 years in prison and Mr. Wiendl junior to 18 years in prison for treason. František Wiendl junior was imprisoned in the Jáchymov region (Eliáš, Nikolaj, „L” in Vykmanov, Rovnost, camp „C”) and since 1956 in the Pankrác prison, where he worked in the project design department, drawing up proposals of state construction projects. He continued in this profession even after he was released in 1960 and he sticked with this job till his retirement. In the present day, he is active in the Sokol and in the Confederation of political prisoners. He is the president of the Confederation in Klatovy.