After the war, my grandma did not understand why she was not allowed to cross the border. They arrested her

Download image

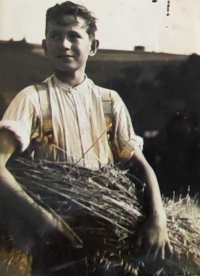

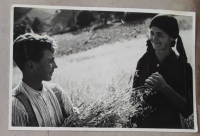

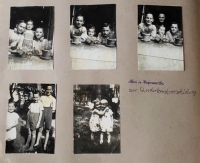

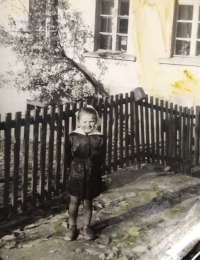

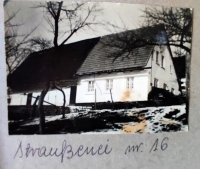

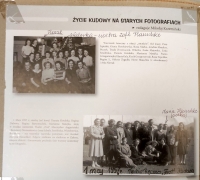

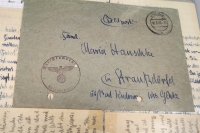

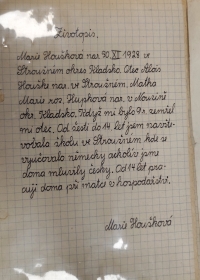

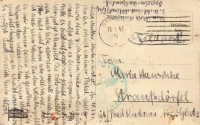

She was born on January 25, 1957 in the Polish spa town of Kudowa-Zdrój to a Polish mother Zofia, née Nowak, and a father of Czech origin with German citizenship. Horst Hauschke came from a family of Kłodzko Bohemians from Stroužné (formerly Straußeney, today Pstrążna). The witness grew up in Pstrążná with her parents and younger sister Elżbieta, they spoke Polish at home. She learned Czech from her grandmother Marie Hauschke, who remained in Pstrążná even after the arrival of the Poles after the Second World War, when Kłodzko fell to Poland. After a two-year gardening school, she worked in a sanatorium in Bukowina. She got married in 1975 and raised four children with her Polish husband. After the fall of communism, she went to work in Germany, later she worked for 15 years in the open-air museum in Pstrążná. In 2015, her aunt Marie Hauschke, who was considered the last Czech woman from Kłodzko, died. The witness was interested in the history of Pstrążná and carefully maintained a family archive. In 2022, she lived in Pstrążná.