I bow down before my brother´s sacrifice but I am not willing to accept it

Download image

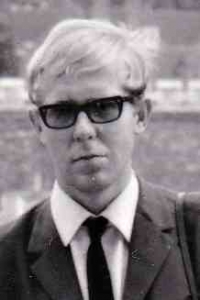

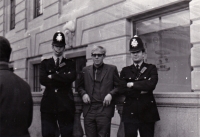

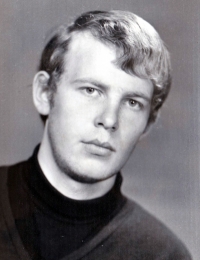

Jaroslav Zajíc was born October 23rd of 1947 in Vítkov in the Opava District. His parents were born in the Highlands and came to Opava in 1945 after the German population had been expelled. His father worked at the pharmacy; his mother was a teacher. On February 25th 1969 his younger brother Jan self-immolated in Wenceslas Square in Praha. Inspired by Jan Palach, he aimed to rally the people against the totalitarian communist regime. Bereaved members of the family were persecuted; his father had been expelled from the Communist party and his mother had to leave the educational system. Both Jaroslav and his younger sister faced discrimination at school and at work. For twenty years the Secret Police quashed anyone who would try to commemorate Jan Zajíc´s deed. Jaroslav graduated from the Technical University of Ostrava´s Faculty of Mechanical Engineering. He has been working at the Vítkovice Ironwork´s research department and at the Mining Construction National Enterprise.