“When I got a bit better, I saw my mom in that window. I would always cry: ´Mom, Mom!´ and run to the window. Later they told me that they had to tie me up, so that I would not fall down from that window, for it was quite high. When I recovered….” Interviewer: “How long did it take for you to recover from camp-fever?” A.Z:. “Well, till May, so it took almost six weeks. A long, really long time, and Magda stayed there because of me, because some transports were already leaving. Transports bound for Czechoslovakia, Poland, the transport trains, wagons with people who were found in concentration camps, they found many people. And she waited till I got better, that’s obvious, and I eventually somehow recovered: my weight was 32 kg, and I was sixteen. And bald, without hair, but alive! They treated my legs also, I had them in terrible shape, because of the frost and ice, and the wounds on my legs were now partly healed. Then we boarded a transport, so we got on a train in Bydžov, I still have our documents from there, my sister had obtained the papers for us to prove our identity and origin, and my sister met this Markovič (her future husband) at one of the railway stations, I don’t remember where exactly, for I was still very exhausted and sleepy. So they met and he told her he was going to Krnov, so we went to Krnov as well. But we arrived there later, because we had made a stop in Humenné before, but we did not find any family members there. We went to Hungary.

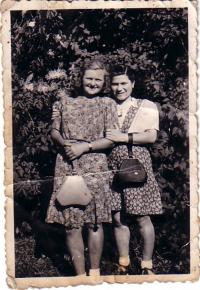

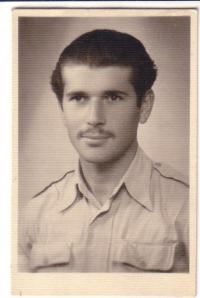

I will tell you one great story about Hungary, where I had had two aunts, Honiko and Elenka, my mother’s sisters, none of them survived. They were no longer alive, but their children, the son, who was a doctor, was now studying, and another studied to become a solicitor, and the two sons allegedly escaped to America. So hopefully they saved themselves, but I don’t know whether they are alive, the Red Cross searched for them, but did not find them, so I don’t know, but people there, when we asked, told us that they had survived. And when I recovered and we settled in Krnov, we kept going to Budapest to look for our family, we went to different places trying to locate at least some relatives, we did not know where our father was, we had no idea where our dad was. My mother was in Auschwitz, but we did not know anything about our father. So we were in Hungary, in the town of Gorojte, where aunt Etelka had lived, and the house had been bombed. There was a heap of ruins, just ruins where the house had been. And I and my sister still wore this clothing with stripes, because nobody gave us any other clothes, and with scarves on our heads, because we did not have hair, or at least I did not. So we walked around this ruin and cried, we both cried and then we saw a Russian soldier walking by. And because in that village, in Prinica or what it was called, where I was in a hospital and my sister, and my sister lived together with others in a house, a barrack, and the Russians had been coming in and raping them, one by one, they raped all the girls, including my sister. They were all raped, and then they reported it, so the commander put a guard at the door, but the guard did the same thing, she could resist if there was just one soldier, but when three or four stormed in, you were not able to do anything, it was terrible. And so we were very afraid of them. And now, when we spotted a Russian, a soldier in a Russian uniform, Magda said: ´Come, we have to run, there is nobody else around, don’t let anything happen.´ So we started to run away, and the soldier called out: ´Hey, hey, wait!´ And he shouted in Hungarian, which was… A Russian uniform and speaks Hungarian. So my sister said: ´Wait, we wait and see, were are two against one.´ And now imagine that, this soldier who was calling us was my brother Vojta, who was looking for our aunt at the same address where we went. And he was walking through Budapest and trying to find out something about his aunts. And suddenly he saw two girls, he did not recognize me, but Magda was older and although she was terribly thin, he recognized our mother’s features in her face, and he said: ´Jesus, that must be Magda!´ Oh my, what a meeting that was, I cannot even describe that! All three of us cried and cried till the evening.”