I didn’t want anything from the regime because I didn’t want the regime to ask me for a favor in return

Download image

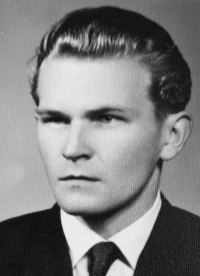

Leo Žídek was born on September 8, 1932, in Dolní Lutyně (in the former district of Fryštát, the present-day district of Karviná). His family was driven out of Lutyně first by the Poles and then by the Germans. The first time, they found shelter in Malenovice pod Lysou Horou, where his father had relatives. The second time, they went to Mirošov nearby Valašské Klobouky and it was here where he spent the war years. Not far from Klobouky lies the village of Smolina, the birthplace of Josef Valčík, who was killed in combat on June 18, 1942, together with the paratroopers who assassinated Reinhard Heydrich. A lot of his relatives were executed in the concentration camp in Mauthausen. After the war, the family returned to Dolní Lutyně again, but because Leo’s father was a functionary of a right-wing party and refused to incorporate his party into the National Front, the family was expelled for a third time from the village by the Communists in 1948. Leo Žídek attended a grammar school in Bohumín and later in Nový Jičín. He was the only one from the entire school who didn’t join the newly-founded Czechoslovak Union of the Youth and this bore dire consequences for him – he wasn’t admitted to the school-leaving exam. As he wished to study at the Stuttgart University, he decided to leave Czechoslovakia and go into exile with his friend, a later editor of the Vyšehrad magazine. Unfortunately, their group was infiltrated by secret state-police agents (StB) and Leo Žídek was arrested by the police on August 18, 1952, while he was returning from one of their meetings (this was shortly before the planned border crossing). He was initially interrogated in Brno before he was escorted together with the other members of the group to the district prison in Ostrava. The trial with the group that counted 11 people and was called “Bradna and Co.” took place in June 1953. Leo Žídek was sentenced to 8 years in prison. By the beginning of September 1953, he was escorted from Olomouc via Pankrác to Vykmanov in the region of Jáchymov. From here, he continued after a few days to the Slavkovsko region where he spent the next year and a half working in the Svatopluk mines. After this, he served his term in the labor camps Vojna and Bytíz in the Příbramsko region. Thanks to amnesty policies, he was released three months prior to the expiration of his term. After his return to Ostrava, he worked as a tile setter. In the meantime he managed to complete his compulsory military service and in 1964 he finally passed his school-leaving examination. He then worked for a traffic construction company until his retirement in 1992. Currently, he’s the chairman of the Ostrava branch of the Confederation of Political Prisoners and in 2006, he was recognized by the Egon Erwin Kisch foundation for his book “Written before the execution” (Psáno před popravou) that he penned and published in 2005.