Anyone who hadn’t gone through their own transformation, cannot honestly talk about what was happening here.

Download image

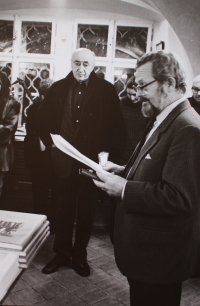

Karol Žižkovský (born July 12, 1938 in Levoča) studied geology and made his living from geology until 1998. At the same time, he devoted practically all his life to collecting prints, journalism and the organization of cultural events. In 1963 he joined the Society of Ex Libris Collectors and Friends. Over time, he started giving lectures about selected artists, write articles about artists for various periodicals (including Čtenář (The Reader), Sítotisk a serigrafie (Screen Printing and Serigraphy), Panorama, Typografie (Typography) or Nové knihy (New Books)), and organize and launch exhibitions in Prague and around the country. In 1972, he started publishing a bibliophile edition of Biblos alongside Josef Runštuk. His publishing activity was monitored by the State Security, but despite warnings, he continued in this activity. When organizing exhibitions, he also tried to support artists who were not perceived positively by the authorities. As a non-party member, he was obliged to join the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, but he joined the Czech People’s Party instead. After the Velvet Revolution, he established a close and long-term collaboration with the renewed Association of Czech Graphic Artists Hollar and in its gallery he would launch up to seven exhibitions every year. Later on he collaborated with the Hotel Villa as curator of regular graphics exhibitions. In addition to journalistic articles and texts of fiction (e.g. a collection of short stories called Elixir of Life and his memoirs entitled Memory Loss? The Unusual and Unusual Memories of a Collector), he also wrote monographs on Daniel and Karel Beneš, Eva Hašková and Jan Maget, Petr Melan and Jindřich Pileček.