Good-bye, mommy, good-bye, dear children, daddy, brothers

Download image

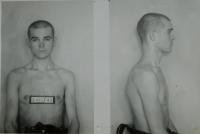

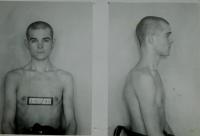

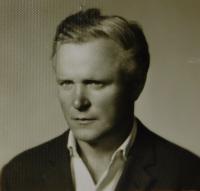

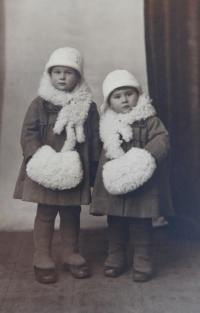

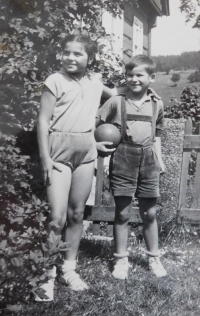

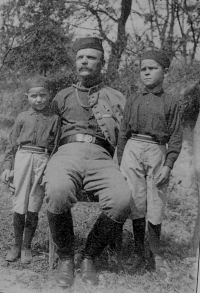

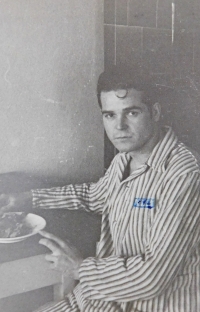

Ludmila Zouharová, née Švédová, was born on September 21, 1946 to Ludmila and Václav Švéda. During the Nazi occupation, her father was imprisoned for several years and her grandfather Josef Kasparides was nearly executed. In 1948 the communist regime nationalized the factory of her grandparents Kasparides. In 1950 her parents’ farm in Lošany became confiscated as well and the family was evicted. Her father Václav Švéda then became a member of the anticommunist resistance group of the Mašín brothers. On May 2, 1955 he was executed in the Pankrác prison in Prague and the urn with his ashes was destroyed. Ludmila’s grandfather František spent seven years in prison and her uncles Vratislav and Zdeněk were imprisoned for eleven years. The property of all of them became confiscated. Her mother Ludmila was arrested as well, and the authorities did not even allow her to part with her husband for the last time. She was sentenced to eighteen years of imprisonment. She had to leave her four-year-old son Radslav and seven-year-old daughter Ludmila at home. She was interned in prisons in Pardubice, Bratislava and Želiezovce where she nearly died do to a serious case of dysentery. She returned from prison after ten years. Nobody wanted to employ her and she thus began working as a janitor in the company OP Prostějov. As her daughter Ludmila recalls, she suffered most from the disrupted relationship with her children which was caused by the long years of separation. When she was sixteen years old, Ludmila had to leave home and in order to secure living for the family she became employed as a worker in a textile factory in Moravská Třebová. She eventually remained working there for nearly forty years until her retirement. In 1968 she married in Moravská Třebová. She had two daughters with her husband, but they divorced in 1982. In 2018 she was living in Linhartice.