Ukrajinský sochař s rakouskými předky: o odsunu z území Polska, dětství sirotka a práci sochaře

Download image

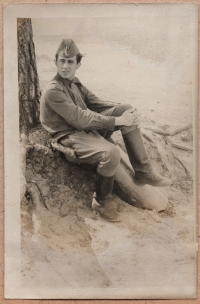

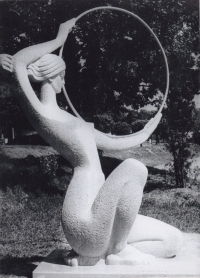

Petro Dzyndra se narodil 28. března 1944 ve městě Jaroslaw (dnes centrum Podkarpatského vojvodství v Polsku) do rakousko-ukrajinské rodiny Ivana (Johana) a Mariyi Schalkových. Jeho otec byl Rakušan, povoláním automechanik. Zemřel v roce 1943 ve Vídni na zápal plic. Jeho matka, Ukrajinka z rodiny Chamiků, kteří dali jméno jaroslawské čtvrti Chamikivka, byla amatérskou herečkou. Rodiče také vychovávali Petrova staršího bratra Romana (narozen 1943). Oba bratři byli registrovaní pod rodným příjmením matky - Chamik. V roce 1945 byli oba společně s rodinami matčiných příbuzných deportováni do sovětské Ukrajiny v rámci poválečné výměny obyvatelstva. Dva týdny nato jejich matka zemřela na tuberkulózu. Petra vychovala jeho teta Olena Verhun, Romana se ujal strýc Volodymyr Chamik. Rodiny byly usídleny v oddělených domech opuštěných polskými rodinami deportovanými do Polska. V roce 1953 zemřel bratr Roman při nehodě. Po škole povolali Petra do sovětské armády, posádkou ve městě Sverdlovsk (dnes Jekatěrinburk, Rusko). Po konci vojenské služby odešel do Lvova, absolvoval přípravné kurzy a nastoupil do Státního institutu designu a užitého umění, kde v roce 1976 promoval, klauzurní prací mu byla socha “Sport” u lvovského paláce kultury. V roce 1968 se oženil s Uljanou Dzyndrou a přijal její příjmení. Od jejího otce, sochaře, se naučil dělat posmrtné masky.