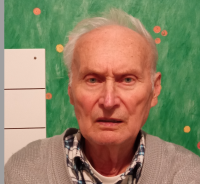

I didn’t know I could have lived so much better

Download image

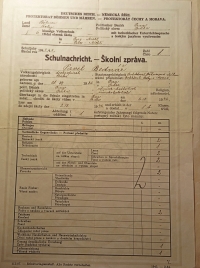

Pavel Bednář was born in Prague-Libeň on 31 July 1936. His father Josef worked as a carpenter and his mother Marie was a trained seamstress but she was a full-time housewife. When Pavel was six years old, his brother Ludvík was born. He first went to school in Michle in 1942. He remembers the air raids on Prague and the events of the Prague Uprising. Following elementary school he entered an electrical engineering apprenticeship and after graduation he started working as a radio mechanic at Tesla Hloubětín. Then he worked as a technician at the Research Institute of Special Radio Engineering at the Tesla National Company and, prior to retirement, at the A. S. Popov Institute in Prague-Lhotka. He married Helena Dupalová in 1966. She came from Třebsín, an area where the Nazis had set up an SS training ground during the war and evicted the whole area. Pavel Bednář has always loved travelling and embraced the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989.