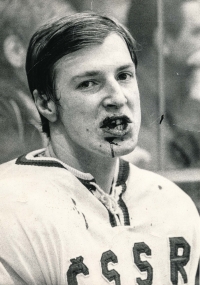

Even the referee wanted to see the Russians humiliated

Download image

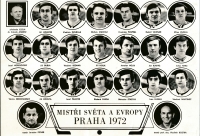

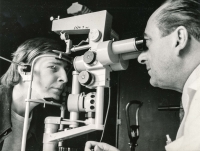

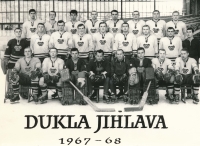

Vladimír Bednář was born on 1 October 1948 in Beroun. Until the age of six, he lived on a farm in the village of Rpety near Hořovice. At the age of six, he moved with his family to Pilsen. His father often went to restaurants where he played cards. To support the family, his mother spent a lot of time working. Vladimír Bednář was a child of the streets, but in time, he found a second home, which became the ice rink. He started playing hockey in Škoda Plzeň, where he spent most of his career as a left defender. He spent two years of military service in Dukla Jihlava, with which he won two championship titles. In 1968, he was captain of the Czechoslovak junior national team when they won the European Championship in Tampere, Finland. In 1969, he represented Czechoslovakia at the World Championships in Sweden, where the national team defeated the Soviet Union twice, eliciting an enthusiastic response from fans who saw the victories as revenge for the occupation in August 1968. He won a bronze medal at the 1970 World Championships and a bronze medal at the 1972 Olympics in Sapporo, Japan. In the same year, he won a gold medal at the World Championships in Prague. In September 1972, he played in a memorable game against the Canadian professional team that ended 3-3 in Prague. In the autumn of 1972, he suffered a severe eye injury that caused him to quit the national team. However, he continued to play in the first league for Škoda Plzeň. He also played in the Norwegian and Yugoslavian top leagues. After the end of his career, he devoted himself to coaching. He also worked as a coach of the Czech national under-20 team. He married at the age of 27, and he and his wife raised a son who also played hockey. In 2021, Vladimír Bednář was living in Pilsen and still coaching at the hockey club in Třemošná.