Be quiet or they will kill us

Download image

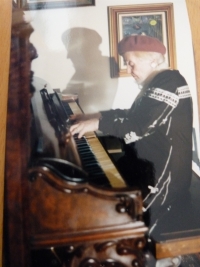

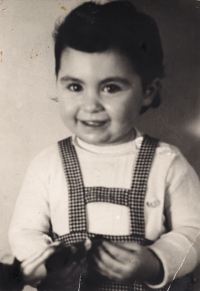

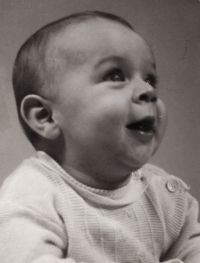

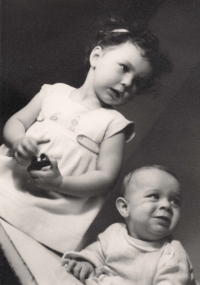

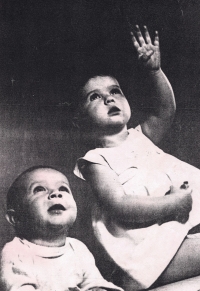

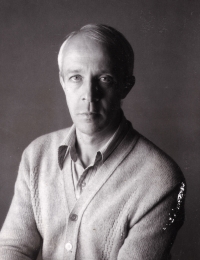

Eva Benešová, née Weiszová, was born to a Jewish family in Prague on 1 October 1940. Her parents Pavel Weisz (1912‒1968) and Pavla Weiszová (1913‒2013) refused to join a transport headed for Terezín and fled from the Protectorate in 1943. They lived in hiding with false documents in Hungary and later made it to Slovakia with the help of their relatives and live to see the liberation in January 1945. Eva has two younger siblings, a brother (1942) and a sister (1945). The family returned to Prague in the autumn of 1945. They adopted a new family name, Kováč. Eva went to school in 1946 and was a church school student for three years, then continued in a school in Londýnská Street. She studied at the High School for Primary School Teachers in Prague-Smíchov. Having graduated, she worked at a school in Uhříněves and later as a warden in a school for disabled and eyesight-impaired children where she enhanced her education. She left the education sector after many years to work as a clerk and secretary. Eva Benešová was married three times; her only Hana daughter was born in 1979. She has been interested in Jewish culture since the 1970s and became a member of the Prague Jewish Community. She founded the Hidden Child Foundation. When her mother died in 2013 she assumed the position of the chairperson of the Association of Jewish Soldiers and Resistance Fighters. Mrs Eva Benešová lives in Prague.