I am grateful to my parents that the horrors of the Holocaust and the loss of loved ones were not the dominant theme in the family.

Download image

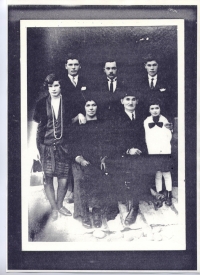

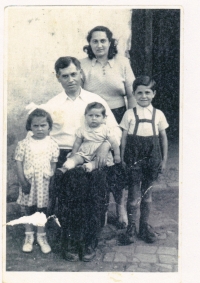

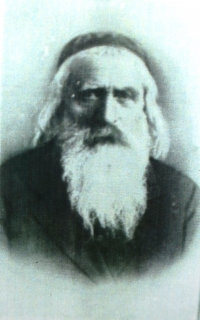

Ivan Bergida was born on February 22, 1943 in Humenné to a pious Jewish family. The father had a tailor’s workshop with his brothers, and thanks to orders to sew police uniforms, they were excepted from Aryanization and deportations. In the spring of 1944, on the basis of a government decree, they were forced to leave eastern Slovakia with numerous relatives from their father’s side and settled in Liptovský Mikuláš. After the suppression of the SNP, the family and one-year-old Ivan hid from the Germans in the mountains during harsh winter. Much of the family did not survive, all seven of the mother’s siblings died. After liberation, they returned to Liptovský Mikuláš and in 1948 left for Košice, where they and other survivors resumed life in a Jewish religious community. Even during the anti-Jewish attitude of the 1950s, the mother ran a traditional Jewish household. Since his parents were only tailors, Ivan had no problem studying at the grammar school and, thanks to his excellent achievements, he studied at the Czech Technical University in Prague from 1961. In June 1965, he had a wedding in the synagogue in Košice, which was the first Jewish wedding since the war. After the August 1968 invasion, he and his wife Marianna immediately decided to emigrate with their two-year-old son to Germany, where her father had lived for several years after his judicial rehabilitation, as he had been convicted in the 1950s of a fabricated Zionist conspiracy. In the early 1970s, when his parents died, Ivan could not come to Czechoslovakia, as he was convicted in absentia after emigration. Until his retirement in 2003, he worked at the IBM research and development center near Stuttgart, and the family is still very happy in Germany. For many years he served on the board of the Jewish community in Stuttgart. He visited Košice with concern for the first time in 1990 and to this day he has a mixed relationship with Slovakia. In retirement, he and his wife live a rich life in Munich, where they moved to be with their son. The daughter lives in the USA and they have a total of six grandchildren.