And then all we could hear were the shots.

Download image

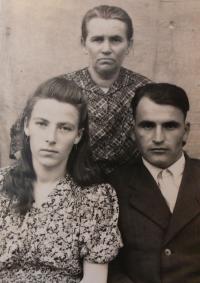

Nina Bilijenková, née Veřbovská, was born in 1929 in the village of Chorov in Volhynia, into a farmer’s family. She grew up in Chorov, later living in the Czech town of Mirohošť, where she stayed even after most of the original inhabitants were deported to Czech land. In 1939, her family became the target of Bolshevik repression - she lost her home in Chorov and she was threatened with deportation to Siberia. During the war, Nina Bilijenková was witness to the repression of Jews and the robbing of civilians by groups of Ukrainian nationalists. In 1947, she married Dmitrij Bilijenko, a Soviet soldier, living with him in Volhynia till 1966, and then until his death in 1990 in Hoštka, Litoměřice district. They both worked in the paper mill in Štětí. They had two sons, Jiří and Vladimír.