Later on I regretted that I didn’t go. I could have been a lady there, I slavered on the field here. Then the Communists came and took everything from us.

Download image

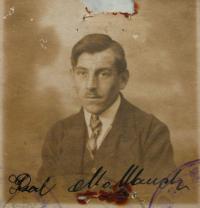

Marie Blabolilová, née Matauchová, was born in a mixed Czech-German family in Nebužely in Mělník region on July 13th, 1923. Her mother Marie, née Bělinová, was Czech and her father Karel Matauch was of the German origin. Marie was the first-born daughter. She has got a sister Emilie, married Hatlová, who is two years younger. The family lived in nearby Konrádov in Kokořín valley since 1927. Marie Matauchová attended German primary school in Konrádov first. However, she did her eighth year in a Czech school in Kladno. Then she went on to the girl’s high school in Šluknov, in short just high school, to learn to keep the house and look after the family. Her father had to join up the Wehrmacht (Defence Force) in 1941. Marie and her mother ran the whole farm since then. Karel Matauch survived the war but was arrested on his way home at Tanvald. He got from the prison camp in Frýdlant to Poland and had to work in a mine where he died because of his severe injury. The Soviet Army reached Konrádov and its surroundings in May 1945. The arrival of soldiers at the region populated mainly by the Germans posed a great danger especially to all girls and younger women. Local inhabitants had to tolerate rages of different plundering groups later. Marie, her mother and sister were not deported to Germany in the end and they could stay in Czechoslovakia. However, Granny Matauch met her fate even if she was 76 years old at that time. Marie Matauchová met a commander of the Soviet garrison, the first lieutenant Vladimír Orlov, in Mšeno in 1945. Their daughter Marie was born in 1946. Vladimír Orlov was murdered during an attack in Hungary about three years later. Marie married Jaroslav Müller after some years. For a couple of years they ran a farm in Tubož, which was seized by the Germans before. However, they lost the farm due to collectivization. Then she farmed with her mother in Konrádov. She divorced Jaroslav Müller in 1958 and she decided to move with her children to Ústí nad Labem. She already had three daughters at that time - Marie, Jaroslava and Marcela. She got a job in a hospital in Ústí nad Labem. She got married for the third time in 1978. She married Jan Blabolil who worked as an engine-driver.