Ideologically, she did not meet the political requirements for the job of a teacher. She was offered to herd sheep

Download image

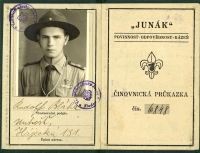

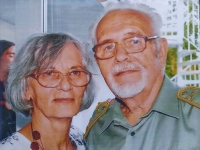

Irena Bláhová, née Valterová, was born on 29 September 1931 in Pilsen as the second daughter of Marie and Jiří Valter. She was a member of Sokol with her parents since she was a child, she went to Scouts. She spent the Second World War with her parents at her grandmother’s house in Unhošt’. She remembers the war years, the liberation and her first love. She fell in love with a Russian soldier. After the war, the children and their parents returned to Sokol. In 1948 she participated in the XIth All-Sokol meeting in Prague. She also performed theatre within Sokol, during which she met her future husband Rudolf Bláha. He was also an enthusiastic scout with the nickname Baghíra. After a year at the teacher’s institute, she graduated from the real grammar school in Kladno. She got her first job in Hostín in Rakovník. In 1952 she married Rudolf and together they raised four children. During their life together they moved frequently, because her husband was a professional soldier. They also lived in Slovakia in Košice and Prešov. Eventually they anchored in Vyškov. They spent the year 1968 in Vyškov and actively participated in social life. However, they were both dismissed from their jobs because of their activities and disagreement with the communist regime. Irena worked as a billing clerk, later as an arranger, Rudolf was discharged from the army and earned a living as a driver and taxi driver. In 1990 they were rehabilitated. Irena returned to education before 1989 as an art teacher. Rudolf Bláha was again an active Boy Scout until 2003, he passed away in 2019. In 2024, Irena Bláha was living in Vyškov-Dědice surrounded by her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.