He sat in the bus that they attempted to hijack to West

Download image

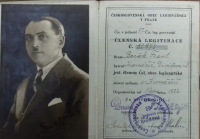

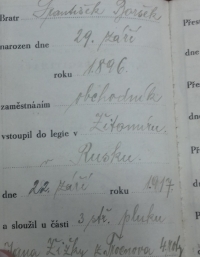

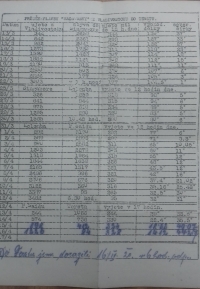

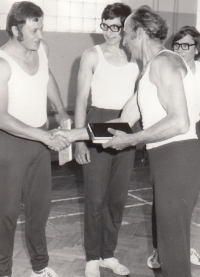

Bedřich Boršek was born August 17, 1928 in Bystřice pod Hostýnem, where his father František Boršek ran a general store. Soon after Bedřich’s birth the family moved to Kroměříž. Because his father had been a legionnaire in Russia during World War I, he was able to apply for a civil service placement and was assigned a job as an IRS clerk in Kašperské Hory. Bedřich and his mother Pavlína stayed in Kroměříž at the beginning of the war, which is where they witnessed the arrival of the German occupation forces. Bedřich spent majority of the war in České Budějovice where the family got an apartment after their father’s return from the Šumava mountains. There he also witnessed the bombing of České Budějovice by the Allies in March 1945. In 1948 he attended the 11th national Sokol festival in Prague where he protested against the emerging Communist regime together with the Sokols from Přerov. He joined the Communist Party in 1966 but left it in1968 already as a protest against the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, which then led to his youngest daughter’s inability to study at a nursing school. In 1984 he was one of the people taken hostage in a hijacked bus that headed towards the state border in Strážný and then to West Germany. At the time of the interview recording (2020) he lived in the nursing home U Hvízdala in České Budějovice and pursued his hobbies.