The most horrible thing was that you had to bow down before the beast

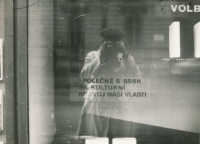

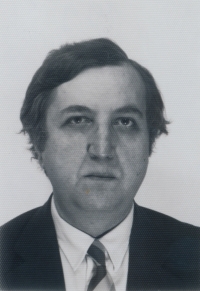

Pavel Bratinka was born on March 14, 1946 in Bratislava and grew up with his mother in Prague. He graduated from the Faculty of Nuclear and Technical Physics of the Czech Technical University in Prague, where an independent spirit reigned in the 1960s. He learned English and regularly visited the US Embassy library. He became a Catholic. In July 1968, he went to Holland to complete his thesis and in late November 1969, he decided to return to the occupied Czechoslovakia. He associated with dissidents, and although he did not sign the Charter 77 manifesto right in the beginning, he worked for it from the very start. He delivered money to the families of dissidents who were in jail, was able to secure replacement for confiscated typewriters, and distributed texts created by Charta. In 1981, he took over the Edice Expedice, a samizdat publisher, and devoted the following two years of his life to it. However, the name had to be changed to Edice Svíce due to conspiratorial reasons. He was twice fired from his job for political reasons; from 1981 until the Velvet Revolution he worked as a cleaner and a boiler operator. The State Security’s kept monitoring him and registered him as an ‘enemy person’. In the 1980s, despite being a boiler operator, he lived a life on an active intellectual: he attended various unofficial lectures held in private flats, Bible studies seminars held by the Kroupa family’s and the so-called underground university in Prague, visited mainly by the French and British scholars. He was a member of the Kampademie – “a renewed Platonic Academy” based in Kampa, Prague. He signed the Charter 77 manifesto in 1988, when he also became a member of the Movement for Civil Freedom (HOS). During the November Revolution he worked for the Civic Forum. One month after the crackdown on the National Avenue, on 17 December 1989, he co-founded the Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA) and became its chairman. After the first free elections, he was a member of the Federal Assembly, and from 1992, the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic. In 1996 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic and became a minister without portfolio in the government of Václav Klaus. In 1998, he resigned from the ODA and, together with Libor Kudláček, he founded the consulting firm Euroffice Praha - Brusel a.s. He lives in Bubenč, Prague.