Not to harm others, so that we all have a nice life

Download image

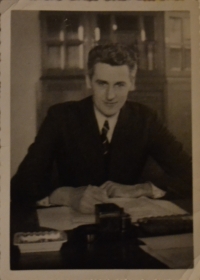

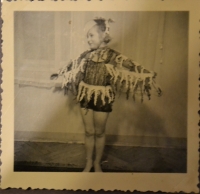

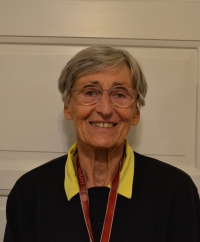

Jitka Bubeníková, born on May 16, 1938, comes from Jablonec nad Nisou. She spent her childhood in Pardubice where she experienced several air raids and bombings. As he mother, Vlasta Holečková, was a famous Czechoslovakian tennis player she was, from early childhood, raised to be a sportswoman. First she played tennis, then became an athlete. Shortly after the communist coup she took part, in June 1948, the Sokol Convention in the Strahov stadium, the last for dozens years to come. In the 1950s, when her mother and her father were sacked from their jobs, the family encountered existential problems. After passing the secondary school leaving exam she went to study the Higher School of Education in Ústí nad Labem and made her living as a primary school teacher. She met with further problems when her brother emigrated unexpectedly in 1972. With her husband Josef Bubeník, whom she met through athletics, she had three sons. One of them, Jan Bubeník, later became the leading figure of the Velvet Revolution. After 1968, her husband was sacked from his position of university teacher. After 2000, she and her husband moved to Poděbrady, where they still live.