We were punished as a warning to everyone

Download image

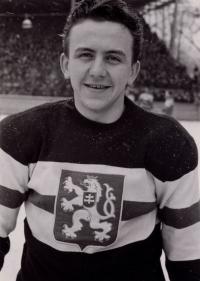

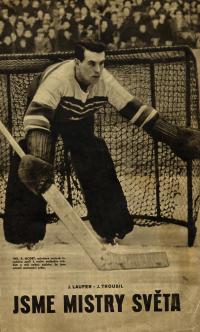

Augustin (Gustav) Bubník was born on the 21st of November 1928 in Prague. As a child, he joined the hockey section of LTC Praha (a successful Prague sports club). At eighteen years of age, he was accepted into the premier league team. From 1947, he became a member of the national team, in 1950 he was the highest scoring player in the hockey league. He was on the national team that won silver at the 1948 Winter Olympics in Saint-Maurice. During a trip to Davos with the LTC club towards the end of that same year, the players were being persuaded to emigrate en masse. After much negotiation the team cast a majority vote deciding not to emigrate, and they all returned to Czechoslovakia. The golden era culminated in them becoming world champions in Sweden in 1949. However, they were not given the chance to defend the title in England the following year. A petty excuse (refused visas for radio reporters) meant that instead of flying to London, the team was forced to sign a proclamation stating that they gave up their place at the championship of their own free will. In this hopeless situation, the team met at a birthday celebration of the son of one of the players in their favourite Prague restaurant U Herclíků on the 13th of March 1950. Harsh words were spoken against the newly established communist regime in reaction to the deceitful radio broadcasts on why the team was not participating. But that was exactly what State Security were waiting for, and with massive police assistance the hockey players were all arrested, Augustin included. At a non-public trial with fabricated charges in October 1950, Augustin was convicted of espionage, high treason and subversion of the state, and sentenced to fourteen years of prison. After serving time in Ruzyně and Bory, he ended up in the uranium mines of the Jáchymov district and later on in Bytíz. He was released on the 23rd of January, 1955 thanks to an amnesty of president Zápotocký. He returned to hockey, but the regime did not allow him to fully develop his career. He played in lower leagues, ending up in Slovana Bratislava. He then decided to try coaching. He studied at the Faculty of Physical Education and Sports of the Charles University in Prague. During the late 1960s he managed to move to Finland, where as the coach of the national team he played an important part in improving the local hockey. When the Finnish team beat Czechoslovakia for the first time in 1967, he bore the brunt of hateful reactions at home. In 1969, he left Finnish hockey for family reasons. He acted as coach for various teams both foreign and domestic throughout the 1970s. He was officially rehabilitated in 1968, but he did not receive full social recognition until after 1989. Augustin Bubník passed away on April, the 18th, 2017.