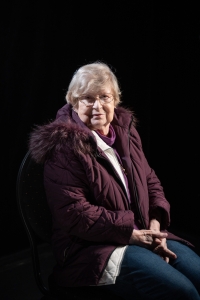

Grandma, tank gun is aiming at your house!

Download image

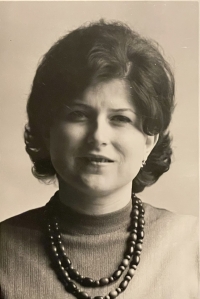

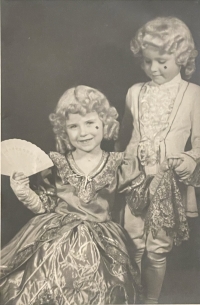

Zdenka Bystrická was born on June 12, 1945 in Ostrava, as the second child of Otakar Novák and Božena, née Tomšíková. She had a sister, Šárka, who was three years older. Her father worked as a financial officer in the mines of Ostrava-Karvinsko, and her mother was a seamstress and later a saleswoman in a women’s fashion salon. Zdenka grew up in a culturally stimulating environment. Her maternal grandmother founded the Hussite Church in Ostrava. She wanted to study chemistry, but her father refused to join the party and she refused join the pioneers, so she did not get into her dream school. After graduating from high school, she went to Olomouc to study mathematics and chemistry. There she met her future husband, Kamil Bystrická from Trenčín. They got married in June 1968. They experienced the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops in Trenčín. They traveled to Ostrava to visit Zdenka’s parents, a tank was parked in front of their house. In September 1969, they started working as teachers at the Ľudovít Štúr Gymnasium in Trenčín. Zdenka had to teach in Slovak. They lured her into the party, but she did not agree. She welcomed the change of regime in November 1989, but the collapse of the republic hurt her. She had to choose between Slovak and Czech citizenship, but in the end she managed to acquire both. She was forced to take exams in the Slovak language. She was offered the position of principal of the gymnasium, but she refused. She taught until 2007, when she retired. At the time of documentation, she is almost 80 years old.