We shouldn’t be content with below-average

Download image

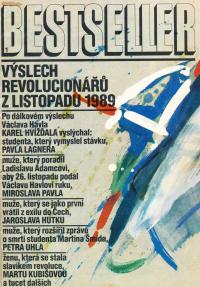

Marta Bystrovová, née Švagrová, was born on 18 December 1947 to Bohumila and Emanuel Švagr. The family soon moved to Prague, where Marta’s father worked as technical support manager at Melantrich, a publishing house. Marta grew up in the streets and suburbs of Smíchov. After graduating from grammar school in 1966 she started as an intern at the daily newspaper Svobodné slovo (Free Word). She was in the hotspot of cultural and political activities in the newspaper’s office on Wenceslas Square for twenty-five years. She mainly wrote in the culture section. In 1968, in the chaotic period when the country was occupied by Warsaw Pact forces, she helped write news reports and distribute special editions of Svobodné slovo. She avoided the political profiling committees in 1970 because she was on maternity leave with her son Ladislav. Her husband Vladimír Bystrov was fired from his job of spokesman for Barrandov Studios. That same year Marta finally decided to abandon her studies of journalism - this was because all the capable and inspiring teachers were forced to leave the school. After maternity leave she returned to her employment at Svobodné slovo. According to her own words, cultural topics and the discovery of new talents became a source of meaningful, joyful, and yet politically harmless journalistic work for Marta within the limitations of normalisation journalism. She signed the petition Several Sentences, and on 17 November 1989 she joined the rest of the editorial staff in protests in Prague-Albertov. She and several colleagues pushed through the decision to publish the news about the brutal suppression of the demonstration on National Avenue together with a statement of disapproval on the title page of the Monday issue of Svobodné slovo, and despite objections from the management, she and the other journalists began providing independent coverage and news reports of the beginnings of the “velvet” coup. The revolutionary enthusiasm made the daily’s print run skyrocket to half a million copies. Marta and her colleagues worked hectically, and their office became one of the focal points of events. In December 1989 she took on the job of deputy editor-in-chief. She worked at the daily until 1991. She was then employed by Lidové noviny (The People’s News; a newspaper with a long-standing tradition - trans.), she accepted an offer to start and create the Saturday supplement. In the years 1995 to 1999 she was engaged by the magazine Týden (The Week). She now writes for the culture section of Lidové noviny.