Rowing earned him an Olympic bronze as well as an interrogation at the StB

Download image

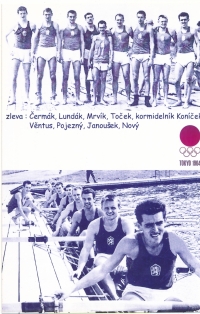

Petr Čermák was born in Prague on 24 December 1942. His mother Marie Dojáčková came from a Czech family living in Vienna. The Dojáčeks moved to Prague’s Vinohrady before the First World War. Father Karel Čermák came from Sedlčany. As for the Second World War, Petr Čermák remembers the roar of Allied bombers bombing Prague in the winter and spring of 1945. Following elementary school, he joined a mechanical engineering school and started rowing with Blesk Praha at about 15 years of age, although the club was called Slavoj in the 1950s. Graduating from high school, he worked at TOS Hostivař for about a month and then enlisted in the military with the Dukla Terezín rowing club. He first had to master basic military training, then he rowed at a top level. In Terezín he met coaches and legendary rowers Vojtěch Hvězda and Václav Kozák. He represented Czechoslovakia as a member of the eight team at the 1962 World Championships in Lucerne, Switzerland. In 1964, he was nominated for the Summer Olympics in Tokyo where the eight team won bronze medals. He received a reward of 1,500 crowns for coming third and another 500 crowns as a bonus from the director of TOS Hostivař. In 1968 he was preparing for the next Olympics in Mexico, and met his future wife Jiřina, who won a silver medal as a field hockey player at the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, during a training camp in Piešt’any. It was in the training camp in Piešt’any that he experienced the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops on 21 August 1968. At the Olympics in Mexico, he came fifth with the eight and then retired from the national team. In the 1970s, he took up field hockey, and was an official of the Slavoj Vyšehrad club where his wife was a player. He worked at TOS Hostivař and the company sent him to West Germany for six months as an engineer, taking part in the design of a new machine for processing industrial diamonds. On return, he refused an offer to join the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) and avoided membership of the Czechoslovak-Soviet Friendship Union. Before 1989, he was summoned for questioning by the State Security Service (StB). The reason was that he gave a tour of Prague to a former fellow rower who had emigrated to the USA. He embraced the fall of the communist regime at the end of 1989 because he was no longer concerned of speaking his mind openly and could quit pretending. He was living in Prague in 2023, a widower with a daughter and two grandchildren.